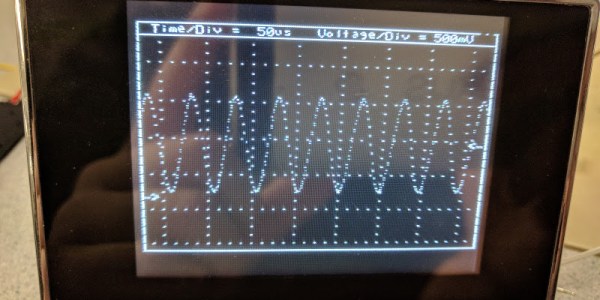

When troubleshooting circuits it’s handy to have an oscilloscope around, but often we aren’t in a lab setting with all of our fancy, expensive tools at our disposal. Luckily the price of some basic oscilloscopes has dropped considerably in the past several years, but if you want to roll out your own solution to the “portable oscilloscope” problem the electrical engineering students at Cornell produced an oscilloscope that only needs a few knobs, a PIC, and a small TV.

[Junpeng] and [Kevin] are taking their design class, and built this prototype to be inexpensive and portable while still maintaining a high sample rate and preserving all of the core functions of a traditional oscilloscope. The scope can function anywhere under 100 kHz, and outputs NTSC at 30 frames per second. The user can control the ground level, the voltage and time scales, and a trigger. The oscilloscope has one channel, but this could be expanded easily enough if it isn’t sufficient for a real field application.

All in all, this is a great demonstration of what you can accomplish with a microcontroller and (almost) an engineering degree. To that end, the students go into an incredible amount of detail about how the oscilloscope works since this is a design class. About twice a year we see a lot of these projects popping up, and it’s always interesting to see the new challenges facing students in these classes.

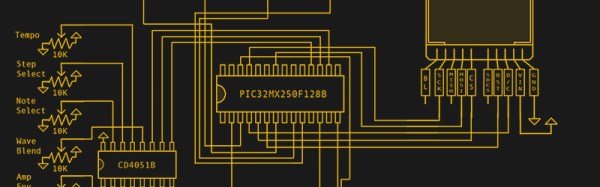

There’s a whole site dedicated to this Vectrex add-on, and the hardware is pretty much what you would expect. There’s a fast PIC32 microcontroller on this cartridge, a USB port, and a dual-port memory chip that’s connected to the Vectrix’s native processor.

There’s a whole site dedicated to this Vectrex add-on, and the hardware is pretty much what you would expect. There’s a fast PIC32 microcontroller on this cartridge, a USB port, and a dual-port memory chip that’s connected to the Vectrix’s native processor.