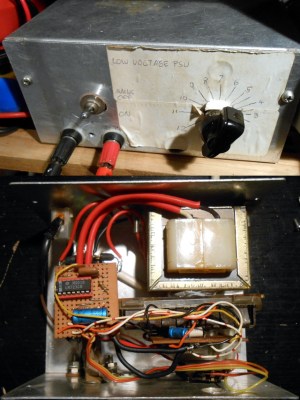

Caveat emptor is good advice in general, but in the wilds of eBay, being careful with what you buy could be life-saving. To wit, we present [Les Wright]’s teardown and very ginger power-up of an eBay tattoo-removal laser power supply.

Given that [Les] spent all of around $100 on this widowmaker, we’re pretty sure he knew what he was getting himself into. But he likely wasn’t quite prepared for the scale of the sketchiness this thing would exhibit. The deficiencies are almost too many to number, starting with the enclosure, which is not only made completely of plastic but assembled from individual sheets of flat plastic stock that show signs of being glued together by hand. Even the cooling water tank inside the case is pieced together this way, which probably led to the leaks that corroded the PCBs. Another assembly gem is the pair of screws the big energy storage capacitor is jammed under, presumably to hold it in place — because nothing says quality like a BOM that can’t spring for a couple of cable ties. Click through the break to read more and see the video.

Continue reading “Fail Of The Week: A Potentially Lethal Tattoo Removal Laser Power Supply”