FTDI are a company known for producing chips for USB applications. Most of us have a few USB-to serial adapters kicking about, and the vast majority of them run on FTDI hardware (or, if we’re honest, counterfeit copies). However, FTDI’s hardware has a whole lot more to offer, and [jayben] is here to show us all how to take advantage of it using Python.

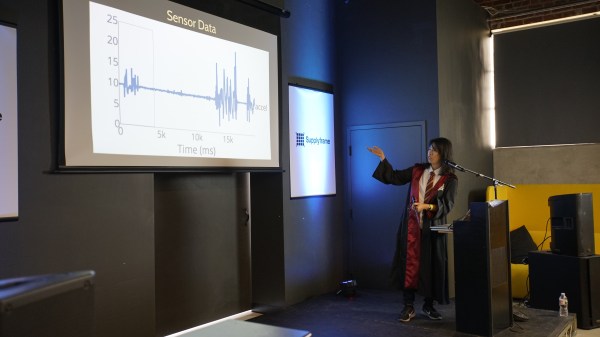

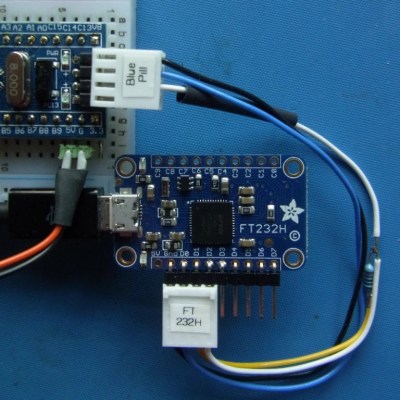

FTDI’s chips have varying capabilities, but most can do more than just acting as a USB-connected COM port. It’s possible to use the chips for SPI, I2C, or even bitbanging operation. [jayben] has done the hard work of identifying the best drivers to use depending on your operating system, and then gone a step further to demonstrate example code for sending data over these various interfaces. The article not only covers code, but also shows oscilloscope traces of output, giving readers a strong understanding of what should be happening if everything’s operating as it should. The series rounds out with a primer on how to use FTDI hardware to speak the SWD protocol to ARM devices for advanced debugging use.

It’s a great primer on how to work effectively with these useful chips, and we imagine there will be plenty of hackers out there that will find great use to this information. Of course, it’s important to always be careful when sourcing your hardware as FTDI drivers don’t take kindly to fake chips.