Were it not for the thin sheath of water and carbon-based life covering it, our home planet would perhaps be best known as the “Silicon World.” More than a quarter of the mass of the Earth’s crust is silicon, and together with oxygen, the silicate minerals form about 90% of the thin shell of rock that floats on the Earth’s mantle. Silicon is the bedrock of our world, and it’s literally as common as dirt.

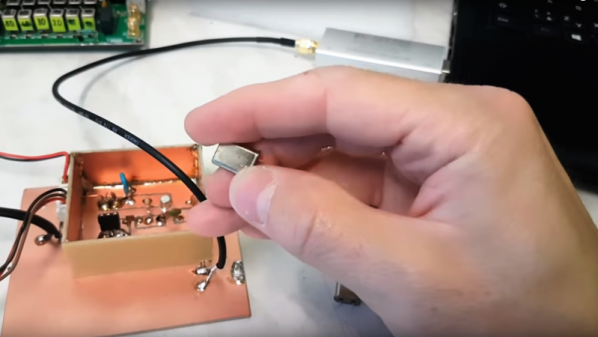

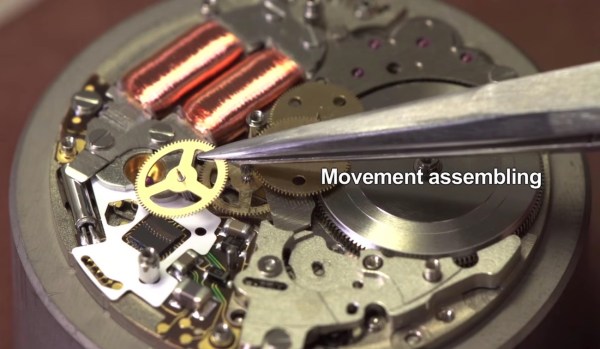

But just because we have a lot of it doesn’t mean we have much of it in its pure form. And it’s only in its purest form that silicon becomes the stuff that brought our world into the Information Age. Elemental silicon is very rare, though, and so getting appreciable amounts of the metalloid that’s pure enough to be useful requires some pretty energy- and resource-intensive mining and refining operations. These operations use some pretty interesting chemistry and a few neat tricks, and when scaled up to industrial levels, they pose unique challenges that require some pretty clever engineering to deal with.

Continue reading “Mining And Refining: Pure Silicon And The Incredible Effort It Takes To Get There”