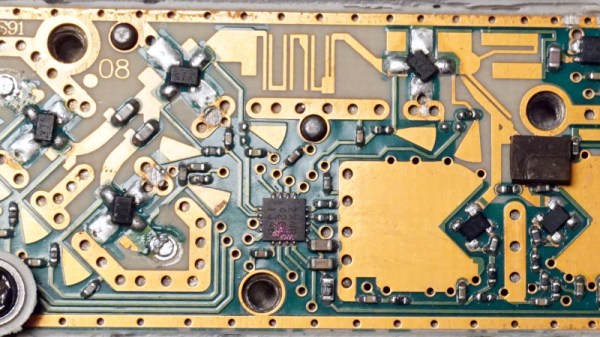

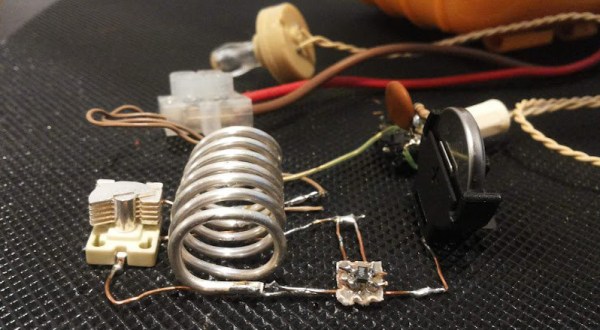

Crystals are key to a lot of radio designs. They act as a stable frequency source and ensure you’re listening to (or transmitting on) exactly the right bit of the radio spectrum. [Q26] decided to use the ProgRock2 “programmable crystal” to build a receiver that could tune multiple frequencies without the usual traditional tuning circuitry.

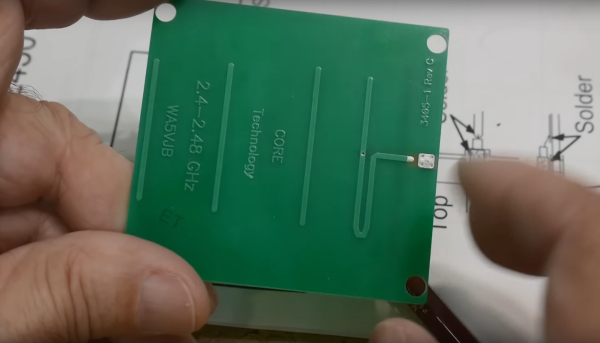

The ProgRock2 is designed as a tiny PCB that can be dropped into a circuit to replace a traditional crystal. The oscillators onboard are programmable from 3.5KHz to 200 MHz, and can be GPS discliplined for accuracy. It’s programmable over a micro USB pot, and can be set to output 24 different frequencies, in eight banks of three. When a bank is selected, the three frequencies will be output on the Clock0, Clock1, and Clock2 pins.There was some confusion regarding the bank selection on the ProgRock2. It’s done by binary, with eight banks selected by grounding the BANK0, BANK1, and BANK2 pins. For example, grounding BANK2 and BANK0 would activate bank 5 (as 101 in binary equals 5). Once this was figured out, [Q26] was on top of things.

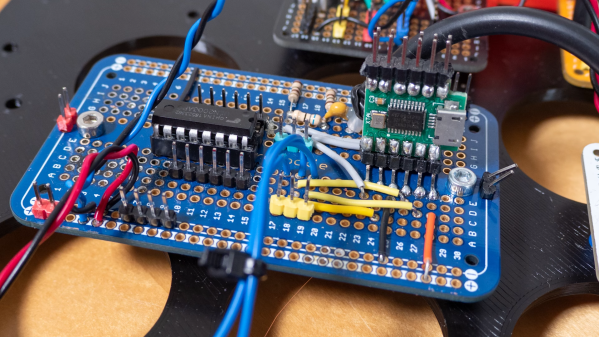

In his design, [Q26] hooked up the ProgRock2 into his receiver in place of the regular crystal. Frequency selection is performed by flipping three switches to select banks 0 to 7. It’s an easy way to flip between different frequencies accurately, and is of particular use for situations where you might only listen on a limited selection of amateur channels.

For precision use, we can definitely see the value of a “programmable crystal” oscillator like this. We’ve looked at the fate of some major crystal manufacturers before, too. Video after the break.

Continue reading “Building A Receiver With The ProgRock2 Programmable Crystal”