In 1971, the United States Navy launched the Omega navigational system for submarines and surface ships. The system used radio frequencies and phase difference calculations to determine global position. A network of eight (VLF) transmitter sites spread around the globe made up the system, which required the cooperation of six other nations.

Omega’s fix accuracy was somewhere between one and two nautical miles. Her eight transmitter stations were positioned around the Earth such that any single point on the planet could receive a usable signal from at least five stations. All of the transmitters were synchronized to a Cesium clock and emitted signals on a time-shared schedule.

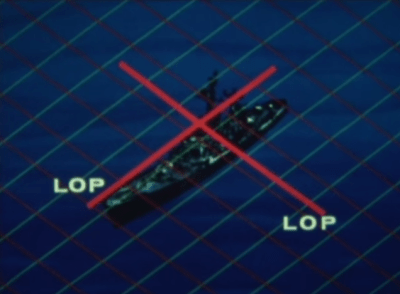

A ship’s receiving equipment performed navigation by comparing the phase difference between detected signals. This calculation was based around “lanes” that served to divvy up the distance between stations into equal divisions. A grid of these lanes formed by eight stations’ worth of overlapping signals provides intersecting lines of position (LOP) that give the sailor his fix.

A ship’s receiving equipment performed navigation by comparing the phase difference between detected signals. This calculation was based around “lanes” that served to divvy up the distance between stations into equal divisions. A grid of these lanes formed by eight stations’ worth of overlapping signals provides intersecting lines of position (LOP) that give the sailor his fix.

In order for the lane numbers to have meaning, the sailor has to dial in his starting lane number in port based on the maps. He would then select the pair of stations nearest him, which were designated with the letters A to H. He would consult the skywave correction tables and make small adjustments for atmospheric conditions and other variances. Finally, he would set his lane number manually and set sail.

Continue reading “Retrotechtacular: The Omega Navigational System”