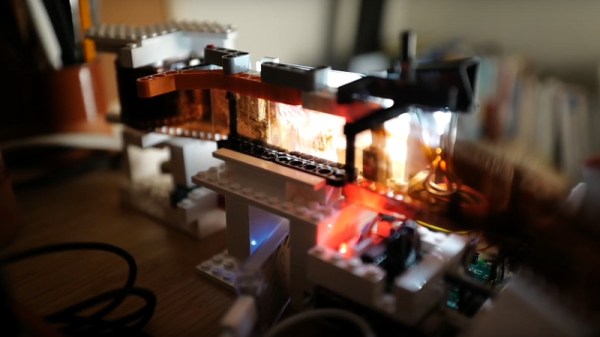

There was a time during the early years of mass digital photography, when a film scanner was a common sight. A small box usually connected to a USB port, it had a slot for slides or negatives. In 2020 they’re a rare breed, but never fear! [Bezineb5] has a solution in the shape of an automated scanner using a Radpberry Pi and a mechanism made of Lego.

The Lego mechanism is a sprocket feeder that moves the film past the field of view from an SLR camera. The software on the Pi runs in a Docker container, and features a machine learning approach to spotting frame boundaries. This is beyond the capabilities of the Pi, so is offloaded to a Google Coral accelerator.

The whole process is automated with the Pi controlling not only the Lego but also the camera, to the extent of retrieving the photos from it to the Pi. There’s a smart web interface to control everything, making the process — if you’ll excuse the pun — a snap. There’s a video of it in action, that you can see below the break.

We’ve featured many film scanner projects over the years, one that remains memorable is this 3D printed lens mount.

Continue reading “Still Got Film To Scan? This Lego And Raspberry Pi Scanner Is For You”