[Ben]’s a 15-year-old who loves engineering and loves taking on new challenges. He’s made some cool stuff over the years, but the high water mark (no pun intended) has to be this impressively documented remote controlled submarine.

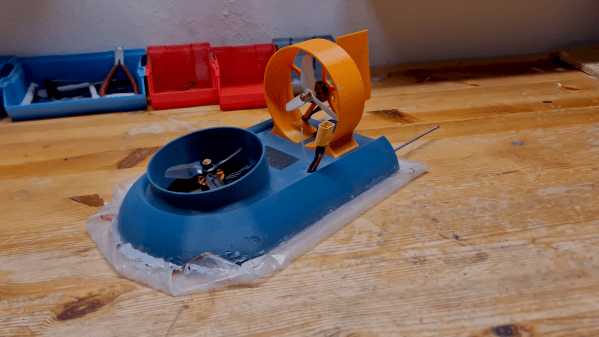

His new build starts off with more research than the actual building. [Ben] spent a ton of time investigating the design of the submarine from its shape, to the propeller system, to the best way to waterproof everything, keeping his sub in tip-top shape. He decides to go with the Russian-style Akula submarine, which is probably the generic look that most of us would think of when we hear the word submarine. He had some interesting thoughts on the propeller system (like the syringe ballast we’ve seen before), and which type of motor to use. In the end, he decided with four pumps that would act essentially as thrusters. fill a chamber with water, allowing the submarine to submerge, or fill with air, making the submarine buoyant, allowing it to resurface.

However, what we found most interesting about his build is how he explains the rationale for all his design decisions and clearly documents his thought process on his project page. We really can’t do [Ben]’s project justice in a short post, so head over to his project page to see it for yourself.

While you’re at it, check out some of these other cool submarine builds that we’ve featured here on Hackaday