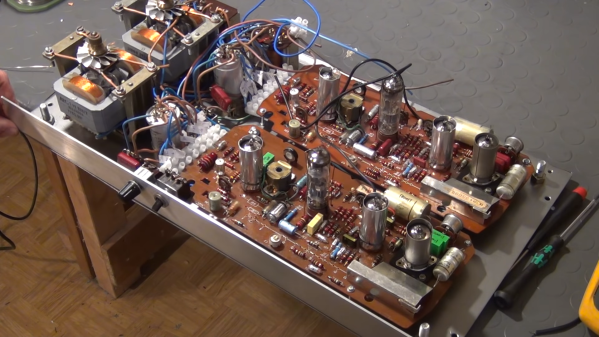

“They don’t build ’em like they used to.” There’s plenty of truth to that old saw, especially when a switch-mode power supply from the 1940s still works with its original parts. But when said power supply is about the size of a smallish toddler and twice as heavy, building them like the old days isn’t everything it’s cracked up to be.

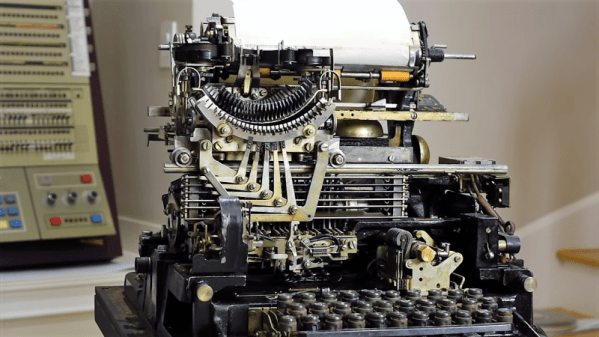

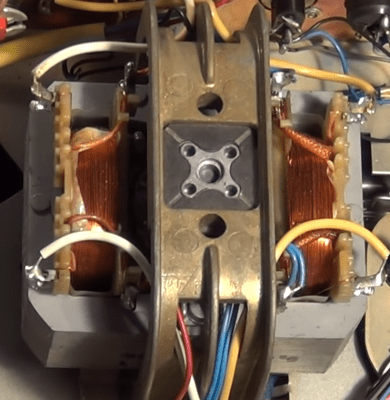

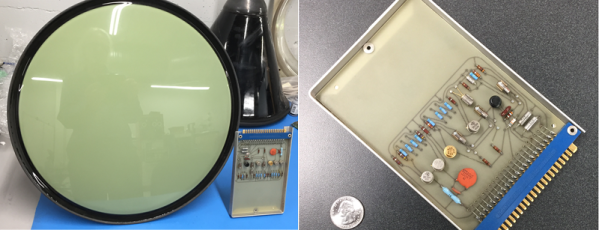

The power supply that [Ken Shirriff] dives into comes from an ongoing restoration of a vintage teletype we covered recently. In that post we noted the “mysterious blue glow” of the tubes in the power supply, which [Ken] decided to look into further. The tubes are Thyratrons, which can’t really be classified as vacuum tubes since they’re filled with various gasses. Thyratrons are tubes that use ionized gas – mercury vapor in this case – to conduct large currents. In this circuit, the Thyratrons are used as half-wave rectifiers that can be rapidly switched on and off by a feedback circuit. That keeps the output voltage fixed at the nominal 140V DC required by the teletype, with a surprisingly small amount of ripple. The video below is from a series on the entire restoration; this one is cued to where the power supply is powered up for the first time. It’s interesting to see the Thyratrons being switched at about 120 Hz when the supply is under load.

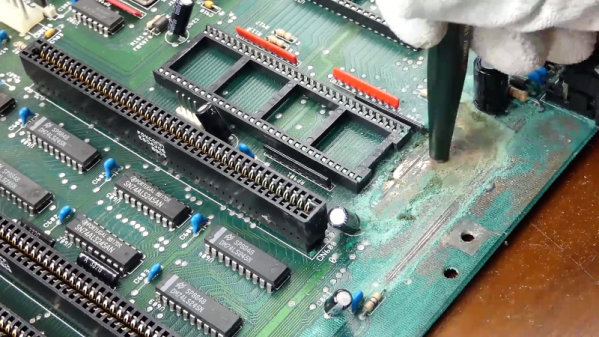

Cheers to [Ken] and his retrocomputing colleagues for keeping the old iron running. Whether the target of his ministrations is a 1974 scientific calculator or core memory from an IBM 1401, we always enjoy watching him work.