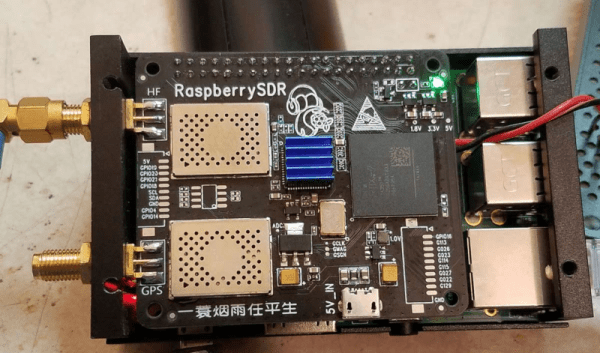

The HackRF is an exceptionally capable software defined radio (SDR) transceiver, but naturally you need to connect it to a computer to actually do anything with it. So the PortaPack was developed to turn it into a stand-alone device with the addition of a touchscreen LCD, a few buttons, and a headphone jack. With all the hardware in place, it’s just a matter of installing a firmware capable enough to do some proper RF hacking on the go.

Enter MAYHEM, an evolved fork of the original PortaPack firmware that the developers claim is the most up-to-date and feature packed version available. Without ever plugging into a computer, this firmware allows you to receive, decode, and re-transmit a dizzying number of wireless protocols. From firing off the seating pagers at a local restaurant to creating a fleet of phantom aircraft with spoofed ADS-B transponders, MAYHEM certainly seems like it lives up to the name.

[A. Petazzoni] recently put together a detailed blog post about installing and using MAYHEM on the HackRF/PortaPack, complete with a number of real-world examples that show off just a handful of possible applications for the project. Jamming cell phones, sending fake pager messages, and cloning RF remotes is just scratching the surface of what’s possible.

[A. Petazzoni] recently put together a detailed blog post about installing and using MAYHEM on the HackRF/PortaPack, complete with a number of real-world examples that show off just a handful of possible applications for the project. Jamming cell phones, sending fake pager messages, and cloning RF remotes is just scratching the surface of what’s possible.

It’s not hard to see why some have already expressed concern about the project, but in reality, none of these capabilities are actually new. This firmware simply brings them all together in one easy-to-use package, and while there might be an argument to be made about proliferation, we all know that the responsibility to behave ethically rests on the user and not the tools.