If you haven’t been following along with Conway’s Game of Life, it’s come a long way from the mathematical puzzle published in Scientific American in 1970. Over the years, mathematicians have discovered a wide array of constructs that operate within Life’s rules, including many that can be leveraged to perform programming functions — logic gates, latches, multiplexers, and so on. Some of these creations have gotten rather huge and complicated, at least in terms of Life cells. For instance, the OTCA metapixel is comprised of 64,691 cells and has the ability to mimic any cellular automata found in Life.

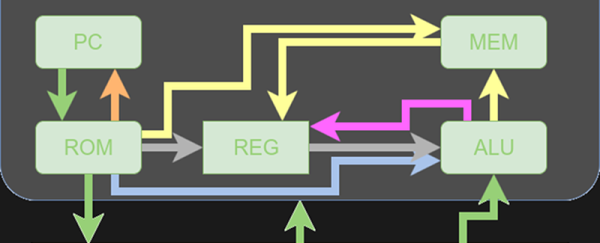

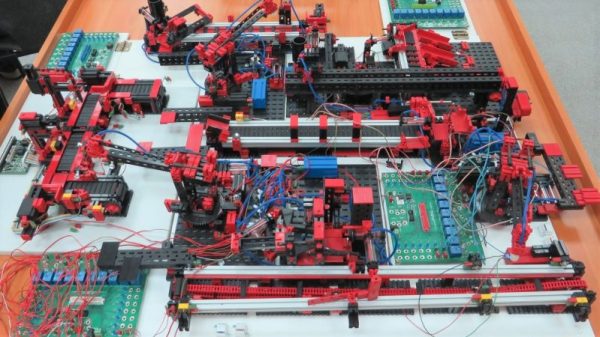

A group of hackers has used OTCA metapixels to create a Tetris game out of Life elements. The game features all 7 shapes as well as the the movement, rotation, and drops one would expect. You can even preview the next piece. The game is the creation of many people who worked on individual parts of the larger program. They built a RISC computer out of Game of Life elements, as well as am assembler and compiler for it, with the OTCA metapixels doing the heavy lifting. (The image at the top of the post is the program’s data synchronizer.

Check out the project’s source code on GitHub, and use this interpreter. Set the RAM to 3-32 and hit run.

For a couple of other examples of Life creations, check out the Game of Life clock and music synthesized from Life automata we published earlier.