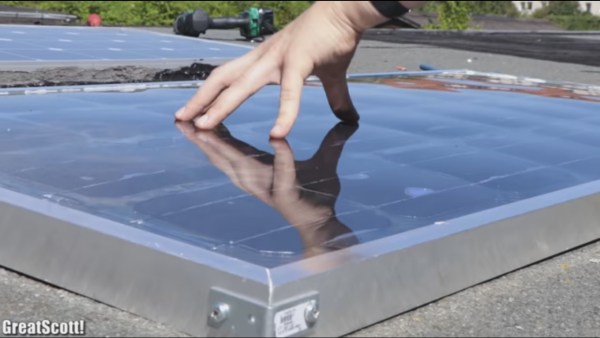

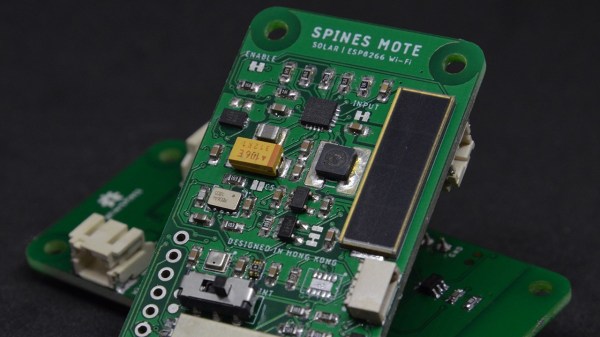

[Mile]’s PTPM Energy Scavenger takes the scavenging idea seriously and is designed to gather not only solar power but also energy from temperature differentials, vibrations, and magnetic induction. The idea is to make wireless sensor nodes that can be self-powered and require minimal maintenance. There’s more to the idea than simply doing away with batteries; if the devices are rugged and don’t need maintenance, they can be installed in locations that would otherwise be impractical or awkward. [Mile] says that goal is to reduce the most costly part of any supply chain: human labor.

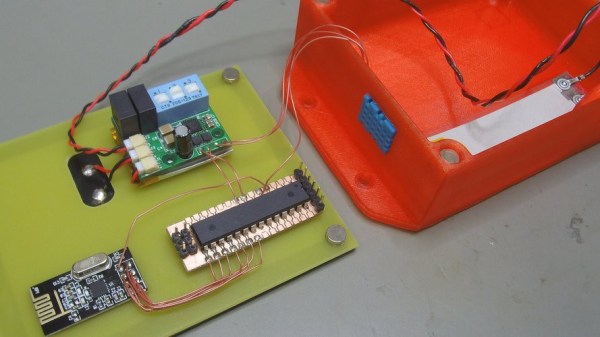

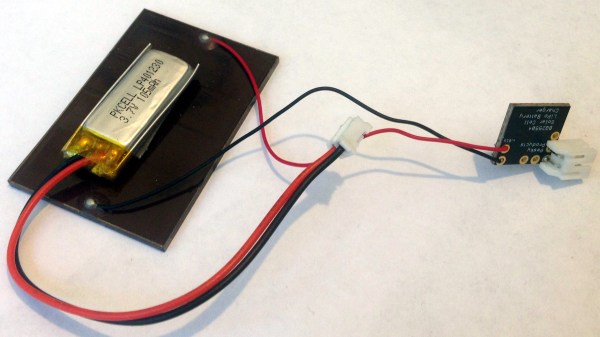

The prototype is working well with solar energy and supercapacitors for energy storage, but [Mile] sees potential in harvesting other sources, such as piezoelectric energy by mounting the units to active machinery. With a selectable output voltage, optional battery for longer-term storage, and a reference design complete with enclosure, the PPTM Energy Scavenger aims to provide a robust power solution for wireless sensor platforms.