[Zhihui Jun] is a name you’re going to want to remember because this Chinese maker has created quite probably one of the most complete open-source robot arms (video in Chinese with subtitles, embedded below) we’ve ever seen. This project has to be seen to be believed. Every aspect of the design from concept, mechanical CAD, electronics design and software covering embedded, 3D GUI, and so on, is the work of one maker, in just their spare time! Sound like we’re talking it up too much? Just watch the video and try to keep up!

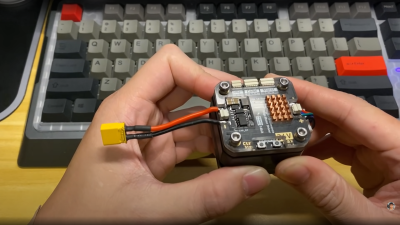

After an initial review of toy robots versus more industrial units, it was quickly decided that servos weren’t going to cut it – too little torque and lacking in precision. BLDC motors offer great precision and torque when paired with a good controller, but they are tricky to make small enough, so an off-the-shelf compact harmonic drive was selected and paired with a stepper motor to get the required performance. This was multiplied by six and dropped into some slick CNC machined aluminum parts to complete the mechanics. A custom closed-loop stepper controller mounts directly to the rear of each motor. That’s really nice too.

Control electronics are based around the STM32 using an ESP32 for Wi-Fi connectivity, but the pace of the video is so fast it’s hard to keep up with how much of the design operates. There is a brief mention that the controller runs the LiteOS kernel for Harmony OS, but no details we can find. The project GitHub has many of the gory details to pore over perhaps a bit light in places but the promise is made to expand that. For remote control, there’s a BLE-connected teaching device (called ‘Peak’) with a touch screen, again details pending. Oh, did we mention there’s a force-feedback (a PS5 Adaptive Trigger had to die for the cause) remote control unit that uses binocular cameras to track motion, with an AHRS setup giving orientation and that all this is powered by a Huawei Atlas edge AI processing system? This was greatly glossed over in the video like it was just some side-note not worth talking about. We hope details of that get made public soon!

The dedicated GUI, written in what looks like Unity, allows robot programming and motion planning, but since those harmonic drives are back-drivable, the robot can be moved by hand and record movements for replaying later. Some work with AR has been started, but that looks like early in the process, the features just keep on coming!

Quite frankly there is so much happening that it’s hard to summarise here and do the project any sort of justice, so to that end we suggest popping over to YT and taking a look for yourselves.

We love robots ’round these parts, especially robot arms, here’s a big one by [Jeremy Fielding], and if you think stepper motors aren’t necessary, because servo motors can be made to work just fine, you may be right.

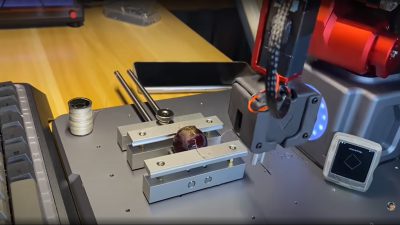

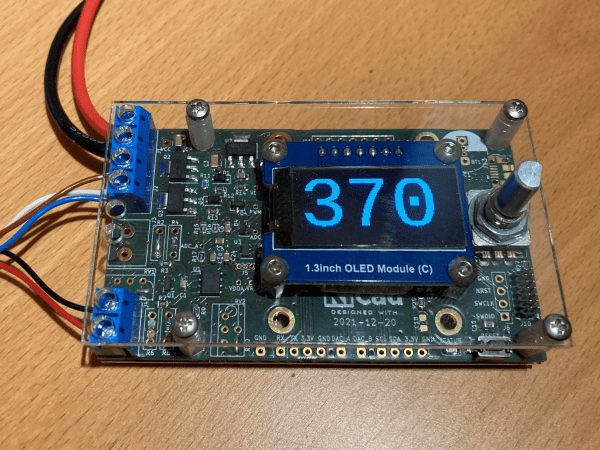

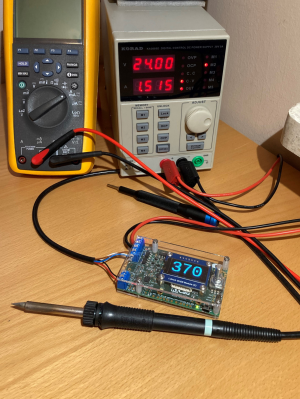

Unbinare’s tools are designed to work in harmony with each other, a requirement for any productive reverse-engineering effort. OI!STER is a general-purpose salvaged MCU research board, with sockets to adapt to different TQFP chip sizes. This board is Maurits’s experience in reverse-engineering condensed into a universal tool, including a myriad of connectors for different programming/debugging interfaces. We don’t know the board’s full scope, but the pictures show an STM32 chip inside the TQFP socket, abundant everywhere except your online retailer of choice. Apart from all the ways to break out the pins, OI!STER has sockets for power and clock glitching, letting you target these two omnipresent Achilles’ heels with a tool like ChipWhisperer.

Unbinare’s tools are designed to work in harmony with each other, a requirement for any productive reverse-engineering effort. OI!STER is a general-purpose salvaged MCU research board, with sockets to adapt to different TQFP chip sizes. This board is Maurits’s experience in reverse-engineering condensed into a universal tool, including a myriad of connectors for different programming/debugging interfaces. We don’t know the board’s full scope, but the pictures show an STM32 chip inside the TQFP socket, abundant everywhere except your online retailer of choice. Apart from all the ways to break out the pins, OI!STER has sockets for power and clock glitching, letting you target these two omnipresent Achilles’ heels with a tool like ChipWhisperer.