What is this world coming to when you spend seven bucks on a digital scale and you have to completely rebuild it to get the functionality you need? Is nothing sacred anymore?

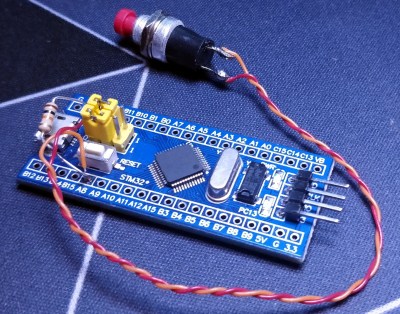

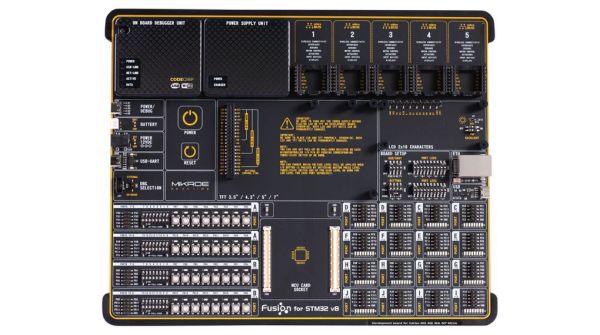

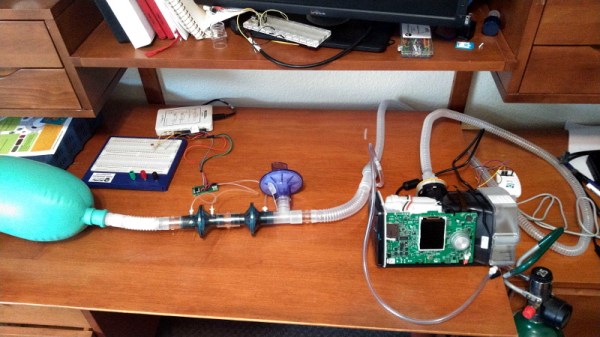

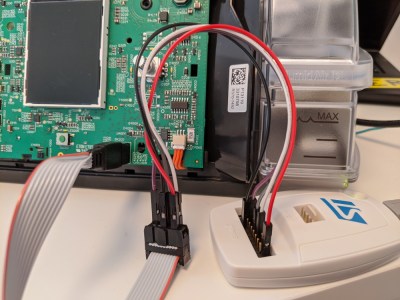

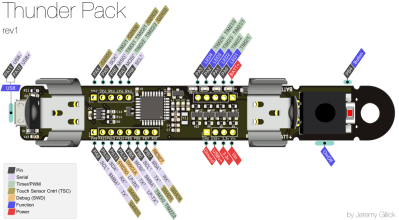

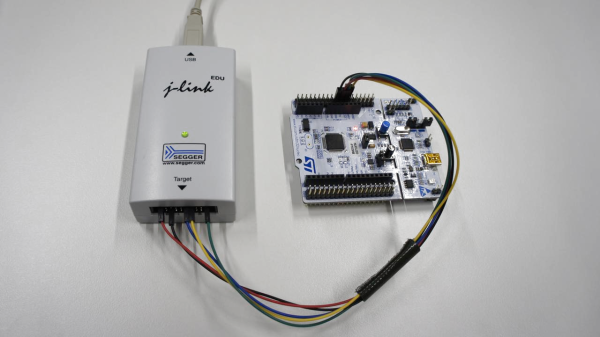

Such were the straits [Jana Marie] found herself in with his AliExpress special, a portable digital scale that certainly looks like it’s capable of its basic task. Sadly, though, [Jana] was looking for a few more digits of resolution and a lot more in the way of hackability. And so literally almost every original component was ripped out of the scale, replaced by a custom PCB carrying an STM32 microcontroller and OLED display. The PCB has a complicated shape that allows the original lid to attach to it, as well as the stainless steel pan and load cell. [Jana] developed new firmware that fixes some annoying traits, for example powering down after 30 seconds, and adds new functionality, such as piece-counting by weight. The video below shows some of the new features in action.

Alas, [Jana] reports that even the original load cell must go, as it lacks the accuracy her application requires. So she’ll essentially end up building the scale from scratch, which we respect, of course. At this rate, she might even try to build her own load cell from SMD resistors too.

Continue reading “Cheap Lab Balance Needs Upgrades, Gets Gutted Instead”