[Joren] recently did some work as part of an electronic music heritage project, and restored an 80s-era NeXTcube workstation complete with vintage sound card, setting it up with a copy of MAX, a graphical music programming environment. But there was one piece missing: MIDI. [Joren] didn’t let that stop him, and successfully created hardware to allow MIDI input and output.

Interestingly, the soundcard for the NeXTcube has an RS-422 serial port and some 8-pin mini DIN connectors. They are not compatible with standard MIDI signals, but they’re not far off, either.

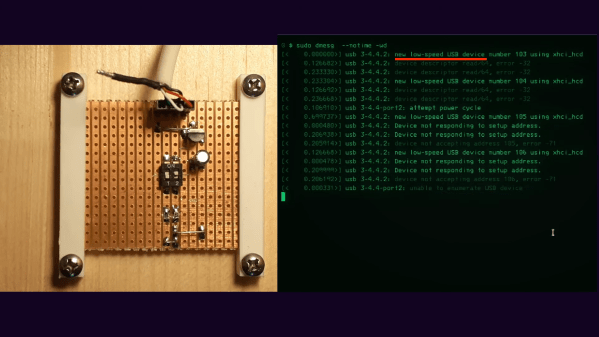

To solve this, [Joren] used a Teensy developer board to act as an interface between classic MIDI devices like keyboards or synthesizers (or even not-so-common ones like this strange instrument) while also being able to accommodate modern MIDI over USB connections thanks to the Teensy’s USB MIDI functionality.

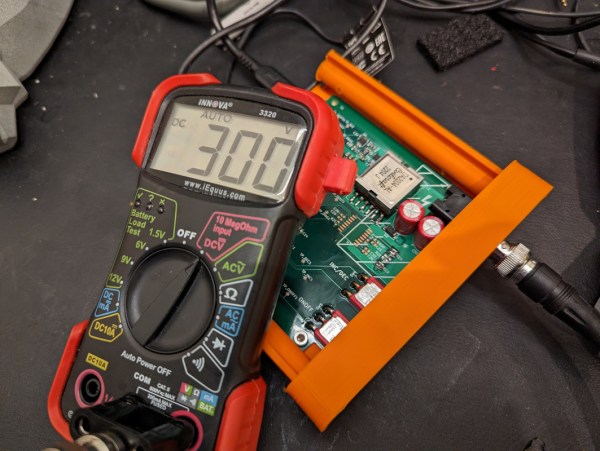

A metal enclosure with a 3D-printed panel rounds out the device, restoring a critical piece of functionality to the electronic music-oriented workstation.

MIDI as a protocol isn’t technically limited to musical applications, though that’s one place it shines. And just in case it comes in handy someday, you can send MIDI over I2C if you really need to.