As [Paul Bardini] explains on the Thingiverse page for his “Micro:Bit Hand Controller”, the Bluetooth radio baked into the BBC’s educational microcontroller makes it an ideal choice for remotely controlling things. You just need to give it a nice enclosure, a joystick, a couple of buttons, and away you go. You can even use the integrated accelerometer as another axis of control. This is starting to sound a bit familiar, especially to gamers.

While it might not come with the Official Nintendo Seal of Quality, the 3D printable enclosure [Paul] has come up with for the Micro:Bit certainly takes more than a little inspiration from the iconic Wii “Nunchuck” controller. He’s jostled around the positions of the joystick and momentary buttons a bit, but it still has that iconic one-handed ergonomic styling.

While it might not come with the Official Nintendo Seal of Quality, the 3D printable enclosure [Paul] has come up with for the Micro:Bit certainly takes more than a little inspiration from the iconic Wii “Nunchuck” controller. He’s jostled around the positions of the joystick and momentary buttons a bit, but it still has that iconic one-handed ergonomic styling.

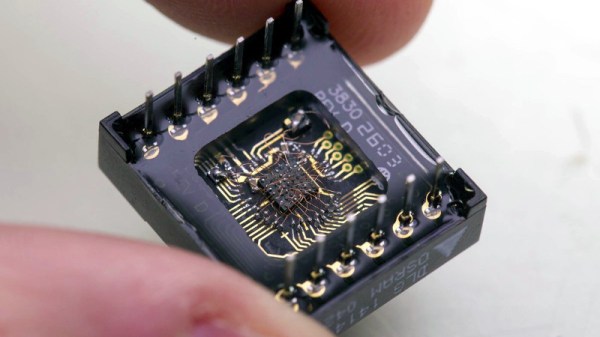

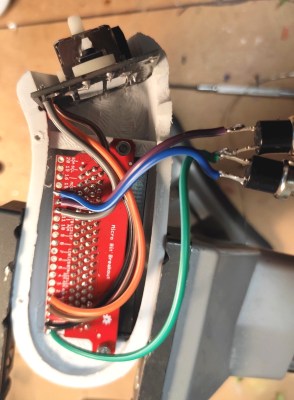

In a particularly nice touch, [Paul] has built his controller around a Micro:Bit breakout board from SparkFun that allows you to plug the microcontroller in via its edge connector. This means you can pull the board out and still use it in other projects. The only other connection to the controller leads to the battery, which uses a two pin JST-PH plug that can easily be removed.

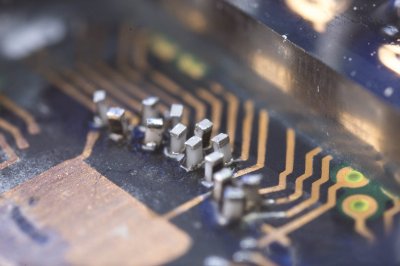

Thanks to this breakout board, the internal wiring is exceptionally simple. The joystick (the type used in a PS2 controller) and the buttons are simply soldered directly to pins on the breakout board. No passives required, just a few short lengths of flexible wiring to snake through the printed enclosure.

The Thingiverse page only has the STLs for the two halves of the controller, and no source code for the Micro:Bit itself. But it shouldn’t be terribly hard to piece together the basic functionality with example code that’s floating around out there. Especially since you can run Python on them now. Of course, you could also add Bluetooth to the original Wii version if you’re not looking to reinvent the wheel nunchuck.