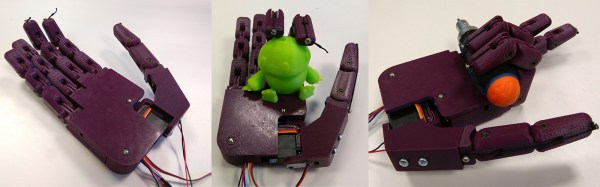

Hands can grab things, build things, communicate, and we control them intuitively with nothing more than a thought. To those who miss a hand, a prosthesis can be a life-changing tool for carrying out daily tasks. We are delighted to see that [Alvaro Villoslada] joined the Hackaday Prize with his contribution to advanced prosthesis technology: Dextra, the open-source myoelectric hand prosthesis.

Dextra is an advanced robotic hand, with 4 independently actuated fingers and a thumb with an additional degree of freedom. Because Dextra is designed as a self-contained unit, all actuators had to be embedded into the hand. [Alvaro] achieved the necessary level of miniaturization with five tiny winches, driven by micro gear motors. Each of them pulls a tendon that actuates the corresponding finger. Magnetic encoders on the motor shafts provide position feedback to a Teensy 3.1, which orchestrates all the fingers. The rotational axis of the thumb is actuated by a small RC servo.

Dextra is an advanced robotic hand, with 4 independently actuated fingers and a thumb with an additional degree of freedom. Because Dextra is designed as a self-contained unit, all actuators had to be embedded into the hand. [Alvaro] achieved the necessary level of miniaturization with five tiny winches, driven by micro gear motors. Each of them pulls a tendon that actuates the corresponding finger. Magnetic encoders on the motor shafts provide position feedback to a Teensy 3.1, which orchestrates all the fingers. The rotational axis of the thumb is actuated by a small RC servo.

In addition to the robotic hand, [Alvaro] is developing his own electromyographic (EMG) interface, the Mumai, which allows a user to control a robotic prosthesis through tiny muscle contractions in the residual limb. Just like Dextra, Mumai is open-source. It consists of a pair of skin electrodes and an acquisition board. The electrodes are attached to the muscle, and the acquisition board translates the electrical activity of the muscle into an analog voltage. This raw EMG signal is then sampled and analyzed by a microcontroller, such as the ESP8266. The microcontroller then determines the intent of the user based on pattern recognition. Eventually this control data is used to control a robotic prosthesis, such as the Dextra. The current progress of both projects is impressive. You can check out a video of Dextra below.

In addition to the robotic hand, [Alvaro] is developing his own electromyographic (EMG) interface, the Mumai, which allows a user to control a robotic prosthesis through tiny muscle contractions in the residual limb. Just like Dextra, Mumai is open-source. It consists of a pair of skin electrodes and an acquisition board. The electrodes are attached to the muscle, and the acquisition board translates the electrical activity of the muscle into an analog voltage. This raw EMG signal is then sampled and analyzed by a microcontroller, such as the ESP8266. The microcontroller then determines the intent of the user based on pattern recognition. Eventually this control data is used to control a robotic prosthesis, such as the Dextra. The current progress of both projects is impressive. You can check out a video of Dextra below.

Continue reading “Hackaday Prize Entry: Open-Source Myoelectric Hand Prosthesis”