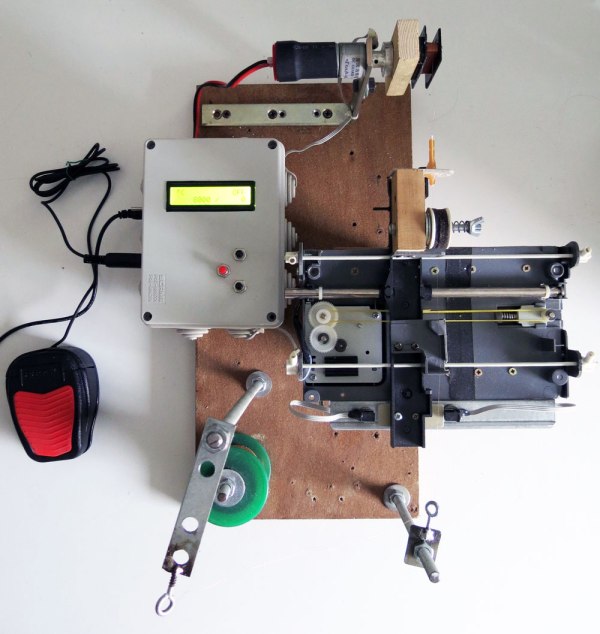

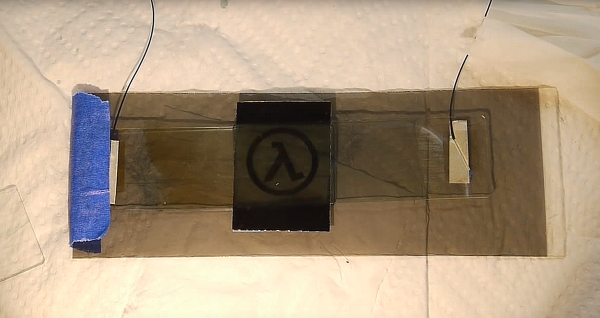

The idea of winding inductive guitar pickups by hand is almost unthinkable. It uses extremely thin wire and is a repetitive, laborious process that nevertheless requires a certain amount of precision. It’s a prime candidate for automation, and while [Davide Gironi] did exactly that, he wasn’t entirely satisfied with his earlier version. He now has a new CNC version that is more full-featured and uses an ATMega8 microcontroller.

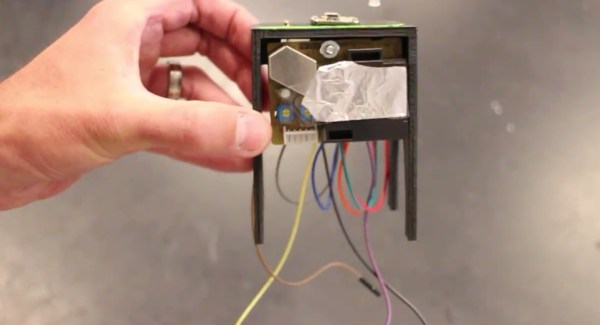

[Davide Gironi]’s previous version took care of winding and counting the number of turns, but it was still an assisted manual system that relied on a human operator. The new upgrade includes a number of features necessary to more fully automate the process, such as a wire tensioner, a wire guide and traverse mechanism (made from parts salvaged from a broken scanner), and an automatic stop for when the correct number of turns has been reached.

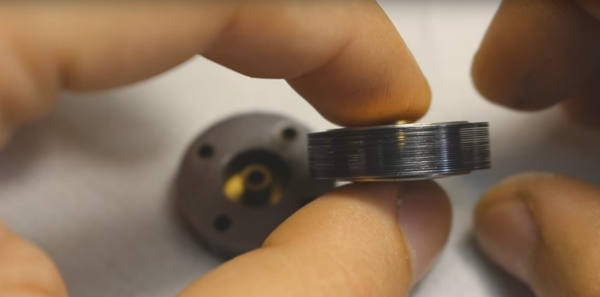

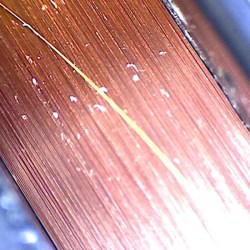

All kinds of small but significant details are covered in the build, such as using plastic and felt for anything that handles the wire — the extremely fine wire is insulated with a very thin coating and care must be taken to not scratch it off. Also, there is the need to compute how far the traverse mechanism must move the wire guide in order to place the new wire next to the previously-laid turn (taking into account the winding speed, which may be changing), and doing this smoothly so that the system does not need to speed up and slow down for every layer of winding.

This system is still programmed by hand using buttons and an LCD, but [Davide Gironi] says that the next version will use the UART in order to allow communication with (and configuration by) computer – opening the door to easy handling of multiple winding patterns. You can see video of the current version in action, below.

Continue reading “CNC Upgrade To Guitar Pickup Winding Machine”

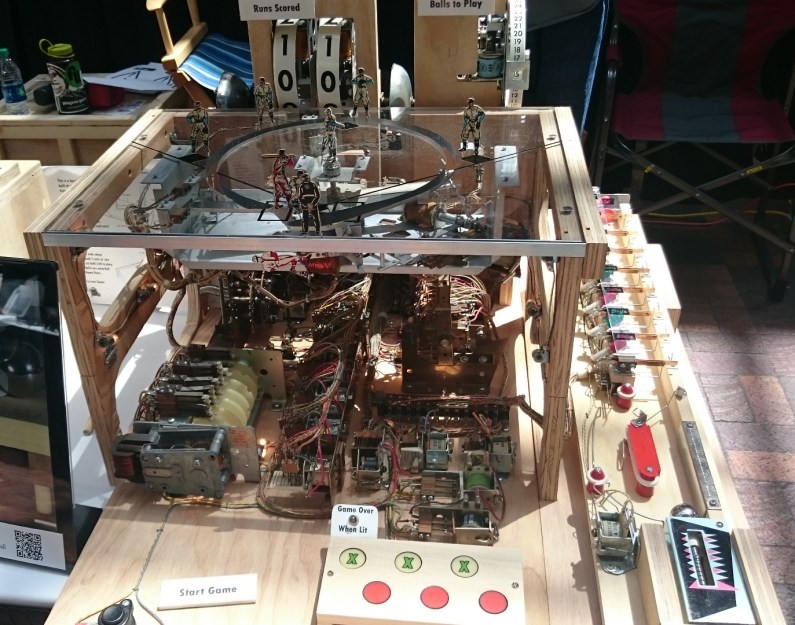

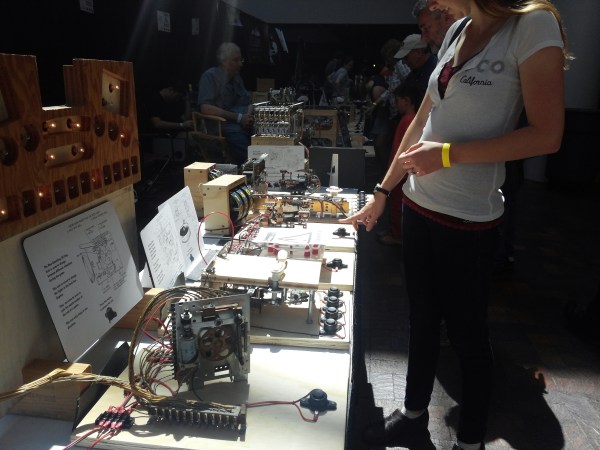

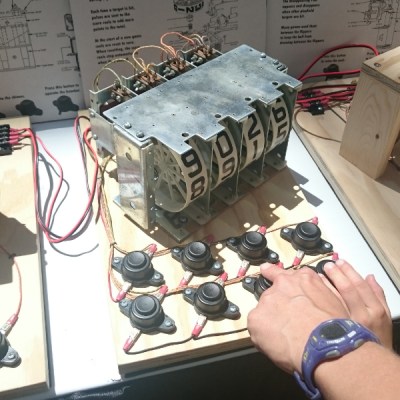

Most of the pieces he has built are single units and simple systems from pinball machines—flippers, chime units, targets, bumpers, and so on—that he affixed to wooden boards so that people can explore them without breaking anything. All of the units are operated using large and inviting push buttons that have been screwed down tight. Each of the systems also has a display card with an engineering drawing of the mechanism and a short explanation of how it works.

Most of the pieces he has built are single units and simple systems from pinball machines—flippers, chime units, targets, bumpers, and so on—that he affixed to wooden boards so that people can explore them without breaking anything. All of the units are operated using large and inviting push buttons that have been screwed down tight. Each of the systems also has a display card with an engineering drawing of the mechanism and a short explanation of how it works.