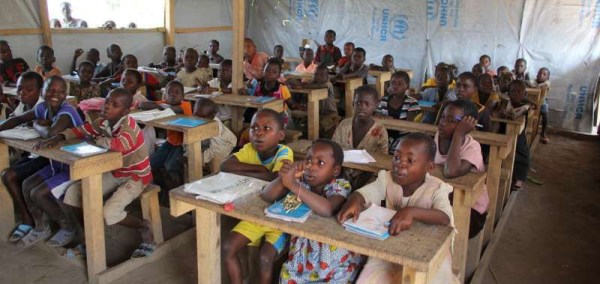

The future of education is STEM, and for the next generation to be fitter, happier, and more productive, classrooms around the world must start teaching programming, computer engineering, science, maths, and electronics to grade school students. In industrialized countries, this isn’t a problem: they have enough money for iPads, Chromebooks, and a fast Internet connection. For developing economies? That problem is a little harder to solve. Children in these countries go to school, but there are no racks of iPads, no computers, and even electricity isn’t a given. To solve this problem, [Eric] has created a portable classroom for his entry into this year’s Hackaday Prize.

Classrooms don’t need much, but the best education will invariably need computers and the Internet. Simply by the virtue of Wikipedia, a connection to the Internet multiplies the efforts of any teacher, and is perhaps the best investment anyone can make in the education of a child. This was the idea behind the One Laptop Per Child project a decade ago, but since then, ARM boards running Linux have become incredibly cheap, and we’re getting to a point where cheap Internet everywhere is a real possibility.

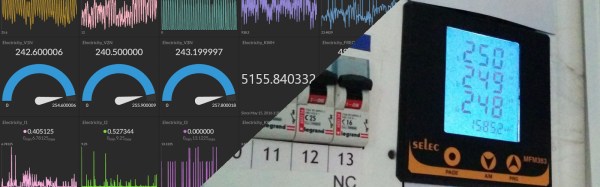

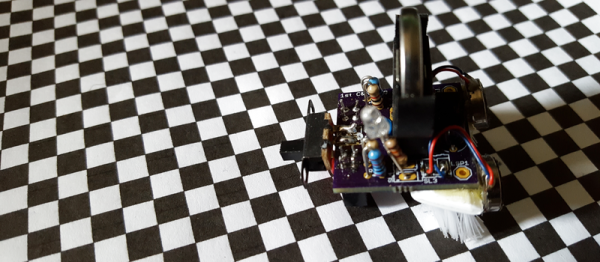

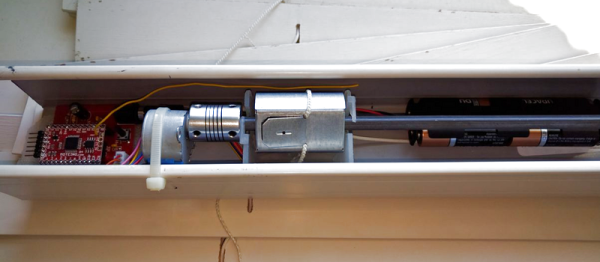

To build this portable classroom, [Eric] is relying on the Raspberry Pi. Yes, there are cheaper options, but the Pi is good enough. A connection to online resources is required, and for that [Eric] is turning to the Outernet. It’s a system that will broadcast educational material down from orbit, using ground stations made from cheap and portable KU band satellite dishes and cheap receivers.

When it comes to educational resources for very rural communities, the options are limited. With [Eric]’s project, the possibilities for educating students on the basics of living in the modern world become much easier, and makes for a great entry into this year’s Hackaday Prize.

Continue reading “Hackaday Prize Entry: Worldwide Educational Infrastructure” →