AI is the new hotness! It’s 1965 or 1985 all over again! We’re in the AI Rennisance Mk. 2, and Google, in an attempt to showcase how AI can allow creators to be more… creative has released a synthesizer built around neural networks.

The NSynth Super is an experimental physical interface from Magenta, a research group within the Big G that explores how machine learning tools can create art and music in new ways. The NSynth Super does this by mashing together a Kaoss Pad, samples that sound like General MIDI patches, and a neural network.

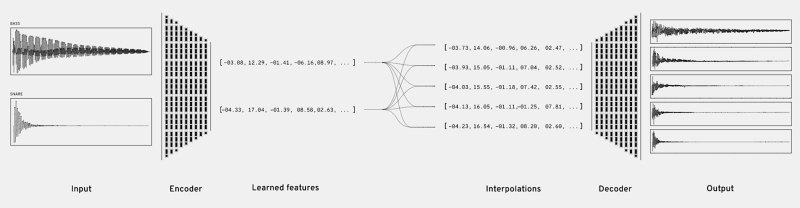

Here’s how the NSynth works: The NSynth hardware accepts MIDI signals from a keyboard, DAW, or whatever. These MIDI commands are fed into an openFrameworks app that uses pre-compiled (with Machine Learning™!) samples from various instruments. This openFrameworks app combines and mixes these samples in relation to whatever the user inputs via the NSynth controller. If you’ve ever wanted to hear what the combination of a snare drum and a bassoon sounds like, this does it. Basically, you’re looking at a Kaoss pad controlling rompler that takes four samples and combines them, with the power of Neural Networks. The project comes with a set of pre-compiled and neural networked samples, but you can use this interface to mix your own samples, provided you have a beefy computer with an expensive GPU.

Not to undermine the work that went into this project, but thousands of synth heads will be disappointed by this project. The creation of new audio samples requires training with a GPU; the hardest and most computationally expensive part of neural networks is the training, not the performance. Without a nice graphics card, you’re limited to whatever samples Google has provided here.

Since this is Open Source, all the files are available, and it’s a project that uses a Raspberry Pi with a laser-cut enclosure, there is a huge demand for this machine learning Kaoss pad. The good news is that there’s a group buy on Hackaday.io, and there’s already a seller on Tindie should you want a bare PCB. You can, of course, roll your own, and the Digikey cart for all the SMD parts comes to about $40 USD. This doesn’t include the OLED ($2 from China), the Raspberry Pi, or the laser cut enclosure, but it’s a start. Of course, for those of you who haven’t passed the 0805 SMD solder test, it looks like a few people will be selling assembled versions (less Pi) for $50-$60.

Is it cool? Yes, but a basement-bound producer that wants to add this to a track will quickly learn that training machine learning algorithms cost far more than playing with machine algorithms. The hardware is neat, but brace yourself for disappointment. Just like AI suffered in the late 60s and the late 80s. We’re in the AI Renaissance Mk. 2, after all.

Continue reading “Google Builds A Synthesizer With Neural Nets And Raspberry Pis.”