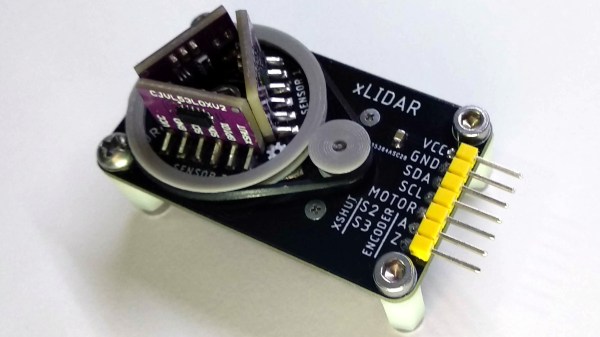

[JRodrigo]’s xLIDAR project is one of those ideas that seemed so attractively workable that it went directly to a PCB prototype without doing much stopping along the way. The concept was to mount a trio of outward-facing VL53L0X distance sensors to a small PCB disk, and then turn that disk with a motor and belt while taking readings. As the sensors turn, their distance readings can be used to paint a picture of the immediate surroundings (at least within about 1 meter, which is the maximum range of the VL53L0X.)

The hardware is made to be accessible and has a strong element of “what you see is what you get.” The distance sensors are on small breakout boards, and the board turns the sensor disk via a DC motor and 3D printed belt drive. Even the method of encoding the disk’s movement and zero position has the same WYSIWYG straightforwardness: a spring contact and an interrupted bare copper trace on the bottom of the sensor disk acts as a physical switch. In fact, exposed copper traces in concentric circular patterns and spring pins taken from an SD card socket are what provide power and communications as the disk turns.

The prototype looks good and sounds like it should work, but how well does it hold up? We’ll find out once [JRodrigo] does some testing. Until then, the board designs are available on the project’s GitHub repository if anyone wants to take a shot at their own approach without starting from scratch.