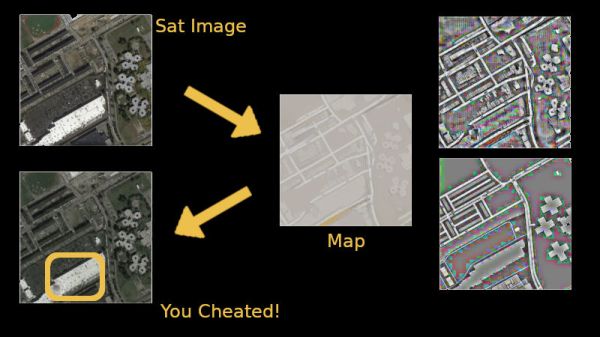

AI today is like a super fast kid going through school whose teachers need to be smarter than if not as quick. In an astonishing turn of events, a (satelite)image-to-(map)image conversion algorithm was found hiding a cheat-sheet of sorts while generating maps to appear as it if had ‘learned’ do the opposite effectively[PDF].

The CycleGAN is a network that excels at learning how to map image transformations such as converting any old photo into one that looks like a Van Gogh or Picasso. Another example would be to be able to take the image of a horse and add stripes to make it look like a zebra. The CycleGAN once trained can do the reverse as well, such as an example of taking a map and convert it into a satellite image. There are a number of ways this can be very useful but it was in this task that an experiment at Google went wrong.

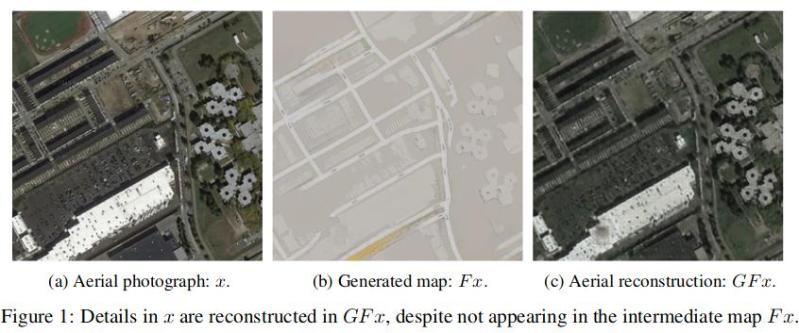

A mapping system started to perform too well and it was found that the system was not only able to regenerate images from maps but also add details like exhaust vents and skylights that would be impossible to predict from just a map. Upon inspection, it was found that the algorithm had learned to satisfy its learning parameters by hiding the image data into the generated map. This was invisible to the naked eye since the data was in the form of small color changes that would only be detected by a machine. How cool is that?!

This is similar to something called an ‘Adversarial Attack‘ where tiny amounts of hidden data in an image or other data-set will cause an AI to produce erroneous output. Small numbers of pixels could cause an AI to interpret a Panda as a Gibbon or the ocean as an open highway. Fortunately there are strategies to thwart such attacks but nothing is perfect.

You can do a lot with AI, such as reliably detecting objects on a Raspberry Pi, but with Facial Recognition possibly violating privacy some techniques to fool AI might actually come in handy.