While at the Hacker Hotel camp in the Netherlands back in February, our attention was diverted to an unusual project. [Niklas Fauth] had bought along a Tesla coil, but it was no ordinary Tesla coil. Instead of the usual tall coil and doughnut-shaped capacity hat it took the form of a stack of PCBs with spacers between them, and because Tesla coils are simply cooler that way, he had it playing music as an impromptu MIDI-driven plasma-ball lousdpeaker. Now he’s been able to write up the project we can take a closer look, and it makes for a fascinating intro not only to double-resonant Tesla coils but also to Galium Nitride transistors.

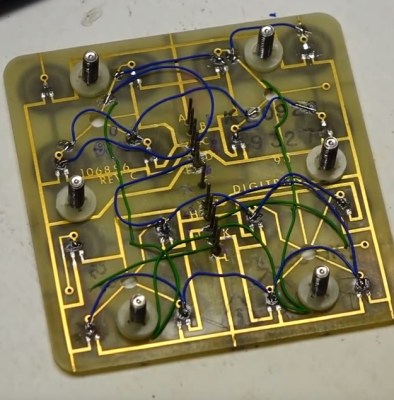

The limiting factor on Tesla coils comes from the abilities of a transistor to efficiently switch at higher frequencies. Few designs make it above the tens of kHz switching frequencies, and thus they rely on the large coils we’re used to. A PCB coil can not practically have enough inductance for these lower frequencies, thus Niklas’ design employs a very high frequency indeed for a Tesla coil design, 2.6 MHz with both primary and secondary coils being resonant. His write-up sets out in detail the shortcomings of conventional MOSFETS and bipolar transistors in this application, and sets out his design choices in using the GaN FETs. The device he’s using is the TI LMG5200 GaN half-bridge driver, that includes all the necessary circuitry to produce the GaN FET’s demanding drive requirements.

The design files can be found in a GitHub repository, and you can see a chorus of three of them in action in the video below. Meanwhile [Niklas] is a prolific hardware hacker whose work has appeared on these pages in the past, so take a look at his ultrasonic phased array and his x-ray image sensor work.