Anyone who pokes around old electronics knows that age is not kind to capacitors. If you’ve got a gadget with a few decades on the clock, there’s an excellent chance that some of its capacitors are either on the verge of failure or have already given up the ghost. Preemptively swapping them out is common in retrocomputing circles, but what do you do if your precious computer has already fallen victim to a troublesome electrolytic?

That’s the situation that [Ronan Gaillard] recently found himself in when he booted up his Mac SE/30 and was greeted with a zebra-like pattern on the screen. The collected wisdom of the Internet told him that some bad caps were almost certainly to blame, though a visual inspection failed to turn up anything too suspicious. Knowing the clock was ticking either way, he replaced all the capacitors on the Mac’s board and gave the whole thing a good cleaning.

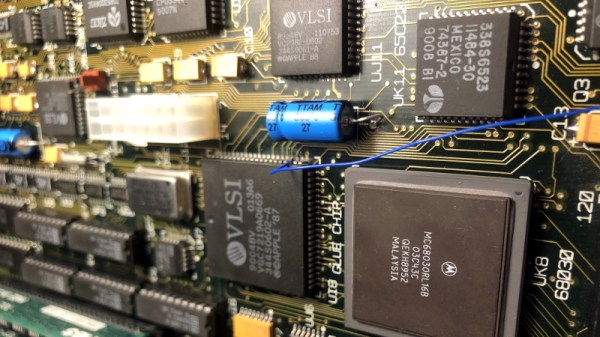

Unfortunately, nothing changed. This caught [Ronan] a bit by surprise, and he took another trip down the rabbit hole to try and find more information. Armed with schematics for the machine, he started manually checking the continuity of all the traces between the ROM and CPU. But again, he came up empty handed. He continued the process for the RAM and Glue Chip, and eventually discovered that trace A24 wasn’t connected. Following the course it took across the board, he realized it ran right under the C11 axial capacitor he’d replaced earlier.

Unfortunately, nothing changed. This caught [Ronan] a bit by surprise, and he took another trip down the rabbit hole to try and find more information. Armed with schematics for the machine, he started manually checking the continuity of all the traces between the ROM and CPU. But again, he came up empty handed. He continued the process for the RAM and Glue Chip, and eventually discovered that trace A24 wasn’t connected. Following the course it took across the board, he realized it ran right under the C11 axial capacitor he’d replaced earlier.

Suddenly, it all made sense. The capacitor must have leaked, corroded the trace underneath in a nearly imperceptible way, and cut off a vital link between the computer’s components. To confirm his suspicions, [Ronan] used a bodge wire to connect both ends of A24, which brought the 30+ year old computer roaring back to life. Well, not so much a roar since it turns out the floppy drive was also shot…but that’s a fix for another day.

It seems like every hardware hacker has a bad capacitor story. From vintage portable typewriters to the lowly home router, these little devils and the damage they can do should always be one of the first things you check if a piece of hardware is acting up.