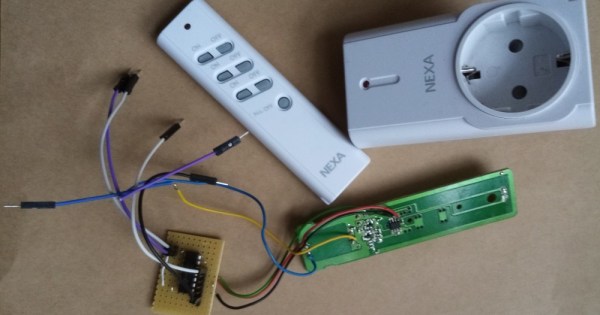

Bending various proprietary devices to our will is a hacker’s rite of passage. When it comes to proprietary wall sockets, we’d often reverse-engineer and emulate their protocol – but you can absolutely take a shortcut and, like [oaox], spoof the button presses on the original remote! Buttons on such remotes tend to be multiplexed and read as a key matrix (provided there’s more than four of them), so you can’t just pull one of the pads to ground and expect to not confuse the microcontroller inside the remote. While reading a key matrix, the controller will typically drive rows one-by-one and read column states, and a row or column driven externally will result in the code perceiving an entire group of keys as “pressed” – however, a digitally-driven “switch” doesn’t have this issue!

One way to achieve this would be to use a transistor, but [oaox] played it safe and went for a 4066 analog multiplexer, which has a higher chance of working with any remote no matter the button configuration, for instance, even when the buttons are wired as part of a resistor network. As a bonus, the remote will still work, and you will still be able to use its buttons for the original purpose – as long as you keep your wiring job neat! When compared to reverse-engineering the protocol and using a wireless transmitter, this also has the benefit of being able to consistently work with even non-realtime devices like Raspberry Pi, and other devices that run an OS and aren’t able to guarantee consistent operation when driving a cheap GPIO-operated RF transmitter.

In the past, we’ve seen people trying to tackle this exact issue, resorting to RF protocol hacking in the end. We’ve talked about analog multiplexers and switches in the past, if you’d like figure out more ways to apply them to solve your hacking problems! Taking projects like these as your starting point, it’s not too far until you’re able to replace the drift-y joysticks on your Nintendo Switch with touchpads!