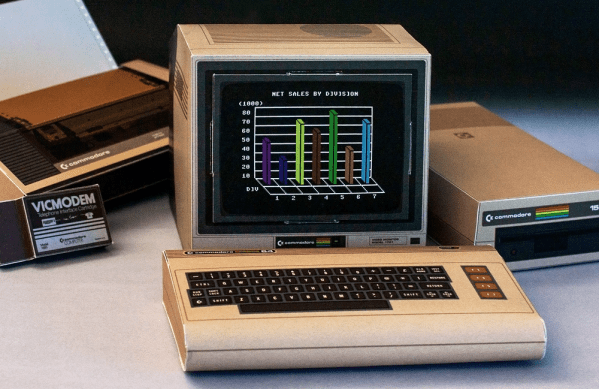

Tired of all your completed (or half-completed) projects cluttering up your workspace? Or you toss them in a box and later forget which box? Well [Another Maker] aka [Develop With Dan] came up with a solution which he dubs Mission Control — panelize your projects and store them in one of many cubbyholes which are provided by a false wall.

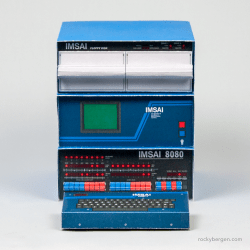

Each project gets a panel and is neatly stored away when not in use. For some project, this could be simply for storage. For other projects, this might serve as a showcase. Occupying the center of Mission Control is a large monitor, presumably a permanent installation. It looks like there are two different sizes of panels, but we wonder whether more and smaller panels might be more useful. As he’s putting this together, we particularly like one piece of advice that [Dan] offers regarding his custom tool, the Cornerator 3000:

Never hesitate to make a jig when you want to repeat something.

[Dan] will be posting this workspace on his GitHub repository along with code and documentation for various projects he posts on YouTube. He’s also proud to have built this system out of 100% recycled material, or as he says, he went dumpster diving. Do you have a good system for storing / displaying projects in your lab? Let us know in the comments below.

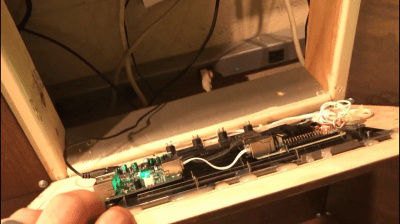

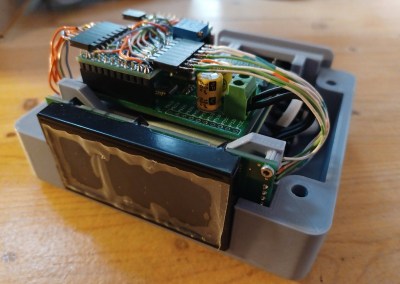

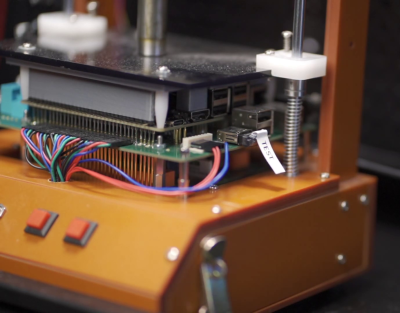

Besides making a bed-of-nails test jig, he also designed a relay multiplexing board to that selects one of the 23 different voltages for measurement. We like his selection of mechanically latching relays in this application — not only does it save power, but it doesn’t subject the test board to any magnetic fields (except when switching state).

Besides making a bed-of-nails test jig, he also designed a relay multiplexing board to that selects one of the 23 different voltages for measurement. We like his selection of mechanically latching relays in this application — not only does it save power, but it doesn’t subject the test board to any magnetic fields (except when switching state).