Interested in making a custom keyboard, but unsure where to start? Good news, because [Jared]’s build log for an adorable “2% Milk” two-key mini-keyboard covers everything you need to know about making a custom keyboard, including how to add optional RGB lighting. The only difference is that it gets done in a smaller and cheaper package than jumping directly in with a full-size DIY keyboard.

[Jared] is definitely no stranger to custom keyboard work, but when he saw parts for a two-key “2% Milk” keyboard for sale online, he simply couldn’t resist. Luckily for us, he took plenty of photos and his build log makes an excellent tutorial for anyone who wants to get into custom keyboards by starting small.

[Jared] is definitely no stranger to custom keyboard work, but when he saw parts for a two-key “2% Milk” keyboard for sale online, he simply couldn’t resist. Luckily for us, he took plenty of photos and his build log makes an excellent tutorial for anyone who wants to get into custom keyboards by starting small.

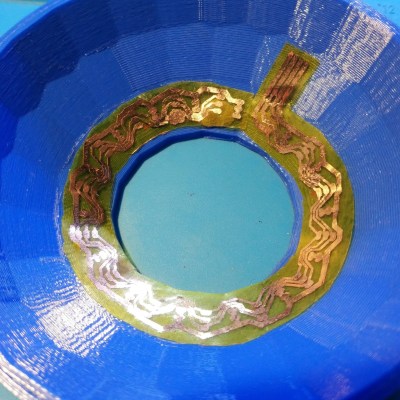

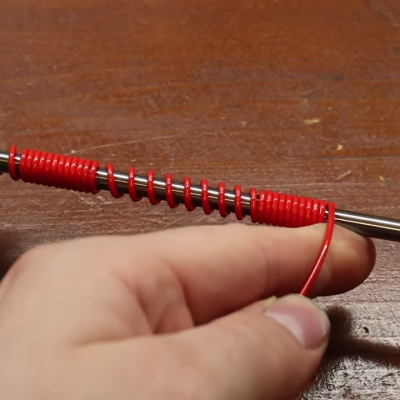

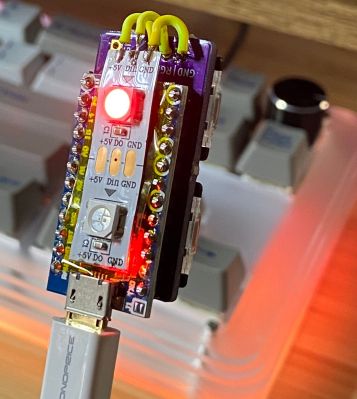

The hardware elements are clear by looking at photos, but what about the software? For that, [Jared] uses a Teensy Pro Micro clone running QMK, an open source project for driving and configuring custom input devices. QMK drives tiny devices like the 2% Milk just as easily as it does larger ones, so following [Jared]’s build log therefore conveys exactly the same familiarity that would be needed to work on a bigger keyboard, which is part of what makes it such a great project to document.

Interested in going a little deeper down the custom keyboard rabbit hole? You can go entirely DIY, but there’s also no need to roll everything from scratch. It’s possible to buy most of the parts and treat the project like a kit, and Hackaday’s own [Kristina Panos] is here to tell you all about what that was like.