What would you get it you mashed up an FPGA and an Arduino? An FPGA development board with far too few output pins? Or a board in the form-factor of Arduino that’s impossible to program?

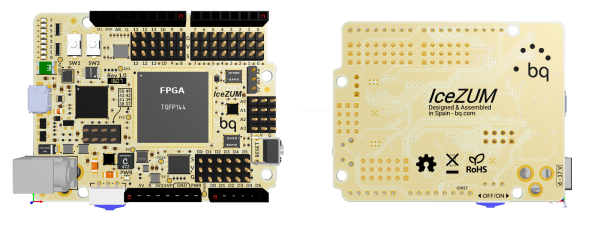

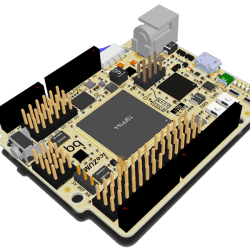

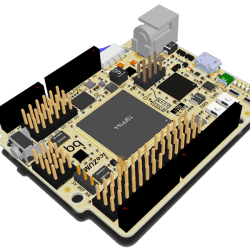

Fortunately, the ICEZUM Alhambra looks like it’s avoided these pitfalls, at least for the most part. It’s based on the Lattice iCE40 FPGA, which we’ve covered previously a number of times because of its cheap development boards and open-source development flow. Indeed, we were wondering what the BQ folks were up to when they were working on an easy-to-use GUI for the FPGA family. Now we know — it’s the support software for an FPGA “Arduino”.

The Alhambra board itself looks to be Arduino-compatible, with the horrible gap between the rows on the left-hand-side and all, so it will work with your existing shields. But they’ve also doubled them with pinheaders in a more hacker-friendly layout: SVG — signal, voltage, ground. This is great for attaching small, powered sensors using a three-wire cable like the one that you use for servos. (Hackaday.io has two Arduino clones using SVG pinouts: in SMT and DIP formats.)

The iCE40 FPGA has 144 pins, so you’re probably asking yourself where they all end up, and frankly, so are we. There are eight user LEDs on the board, plus the 28 I/O pins that end in pinheaders. That leaves around a hundred potential I/Os unaccounted-for. One of the main attractions of FPGAs in our book is the tremendous availability of fast I/Os. Still, it’s more I/O than you get on a plain-vanilla Arduino, so we’re not complaining too loudly. Sometimes simplicity is a virtue. Everything’s up on GitHub, but not yet ported to KiCad, so you can tweak the hardware if you’ve got a copy of Altium.

We’ve been seeing FPGA projects popping up all over, and with the open-source toolchains making them more accessible, we wonder if they will get mainstreamed; the lure of reconfigurable hardware is just so strong. Putting an FPGA into an Arduino-compatible form-factor and backing it with an open GUI is an interesting idea. This project is clearly in its very early stages, but we can’t wait to see how it shakes out. If anyone gets their hands on these boards, let us know, OK?

Thanks [RS] for the tip!