Macro pads are handy for opening up your favorite programs or executing commonly used keyboard shortcuts. But why stop there?

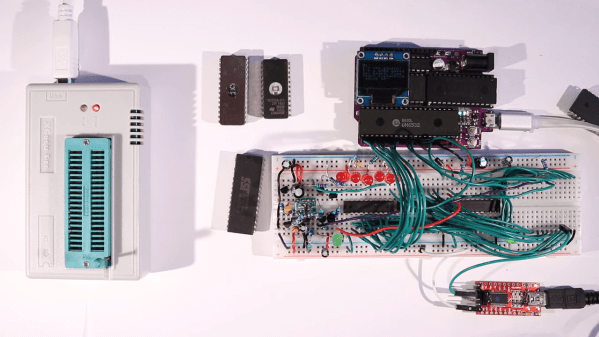

That’s what [Jeroen Brinkman] must have been thinking while creating the Programmer’s Macro Pad. Based on the Arduino Pro Micro, this hand-wired pad is unique in that a single press of any of its 16 keys can virtually “type” out multiple lines of text. In this case, it’s a capability that’s being used to prevent the user from having to manually enter in commonly used functions, declarations, and conditional statements.

For example, in the current firmware, pressing the “func” key will type out a boilerplate C function:

int () { //

;

return 0;

}; // f

It will also enter in the appropriate commands to put the cursor where it needs to be so you can actually enter in the function name. The other keys such as “array” and “if” work the same way, saving the user from having to enter (and potentially, even remember) the correct syntax.

The firmware is kept as simple as possible, meaning that the functionality of each key is currently hardcoded. Some kind of tool that would let you add or change macros without having to manually edit the source code and flash it back to the Arduino would be nice…but hey, it is a Programmers Macro Pad, after all.

Looking to speed up your own day-to-day computer usage? We’ve covered a lot of macro pads over the years, we’re confident at least a few of them should catch your eye.