Smartphones boggle my mind a whole lot – they’re pocket computers, with heaps of power to spare, and yet they feel like the furthest from it. As far as personal computers go, smartphones are surprisingly user-hostile.

In the last year’s time, even my YouTube recommendations are full of people, mostly millennials, talking about technology these days being uninspiring. In many of those videos, people will talk about phones and the ecosystems that they create, and even if they mostly talk about the symptoms rather than root causes, the overall mood is pretty clear – tech got bland, even the kinds of pocket tech you’d consider marvellous in abstract. It goes deeper than cell phones all looking alike, though. They all behave alike, to our detriment.

A thought-provoking exercise is to try to compare smartphone development timelines to those of home PCs, and see just in which ways the timelines diverged, which forces acted upon which aspect of the tech at what points, and how that impacted the alienation people feel when interacting with either of these devices long-term. You’ll see some major trends – lack of standardization through proprietary technology calling the shots, stifling of innovation both knowingly and unknowingly, and finance-first development as opposed to long-term investments.

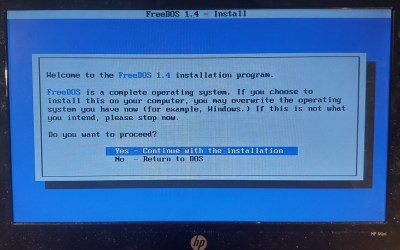

Let’s start with a fun aspect, and that is hackability. It’s not perceived to be a significant driver of change, but I do believe it to be severely decreasing chances of regular people tinkering with their phones to any amount of success. In other words, if you can’t hack it in small ways, you can’t really make it yours.

Continue reading “Smartphone Hackability, Or, A Pocket Computer That Isn’t” →