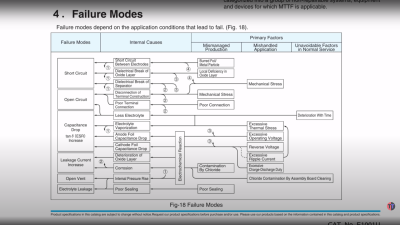

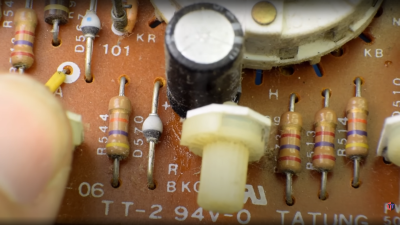

Having acquired some piece of old electronic equipment, be it a computer, radio, or some test gear, the temptation is there to plug it in as soon as you’ve lugged it into the ‘shop. Don’t be so hasty. Those power supplies and analog circuits often have a number of old aluminium electrolytic capacitors of unknown condition, and bad things can happen if they suddenly get powered back up again. After a visual inspection, to remove and replace any with obvious signs of leakage and corrosion, those remaining may still not be up to their job, with the oxide layers damaged over time when sat idle, they can exhibit lower than spec capacitance, voltage rating or even be a dead short circuit. [TechTangents] presents for us a guide to detecting and reforming these suspect capacitors to hopefully bring them, safely, back to service once more.

When manufactured, the capacitors are slowly brought up to operating voltage, before final encapsulation, which allows the thin oxide layer to form on the anode contact plate, this is an electrically driven chemical process whereby a portion of the electrolyte is decomposed to provide the needed oxygen ions. When operating normally, with a DC bias applied to the plates, this oxidation process — referred to as ‘self-healing’ — continues slowly, maintaining the integrity of the oxide film, and slowly consuming the electrolyte, which will eventually run dry and be unable to sustain the insulating oxide layer.

If left to sit un-powered for too long, the anodic oxide layer will decay, resulting in reduced operating voltage. When powered up, the reforming process will restart, but this will be in an uncontrolled environment, resulting in a lot of excess heat and gases being vented. It all depends on how thin the oxide layer got and if holes have started to form. That is, if there is any electrolyte left to react – it may already be far too late to rescue.

If the oxide layer is sufficiently depleted, the capacitor will start to conduct, with a resultant self-heating and runaway thermal decomposition. They can explode violently, which is why there are score marks at the top of the can to act as a weak point, where the contents can burst through. A bit like that ‘egg’ scene in Aliens!

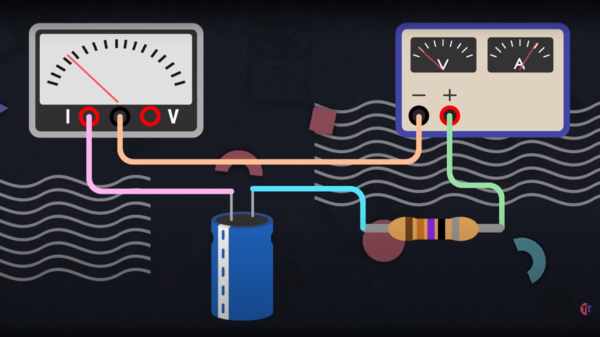

The ‘safe’ way to reform old capacitors is to physically remove them from the equipment, and apply a low, controlled voltage below the rated value to keep the bias current at a low value, perhaps just 2 mA. Slowly, the voltage can be increased to push the current back up to the initial forming level, so long as the current doesn’t go too high, and the temperature is within sensible bounds. The process ends when the applied voltage is at the rated value and the current has dropped off to low leakage values.

A word of warning though, as the ESR of the reformed caps could be a little higher than design, which will result in higher operating temperature and potentially increased ripple current in power supply applications.

We’re really glossing over this subject fast here, but [TechTangents] was kind enough to link to some fine capacitor-related reading for those who need a primer. Here is a US DoD handbook for reforming capacitors with advice on storage shelf life, some tech notes on using electrolytic capactors from chemi-con, and a general capacitor guide from TDK. Reforming caps is nothing new, here’s an previous article about repairs, and something a bit more recent.

Continue reading “Protect Vintage Gear With Easy Capacitor Reforming”