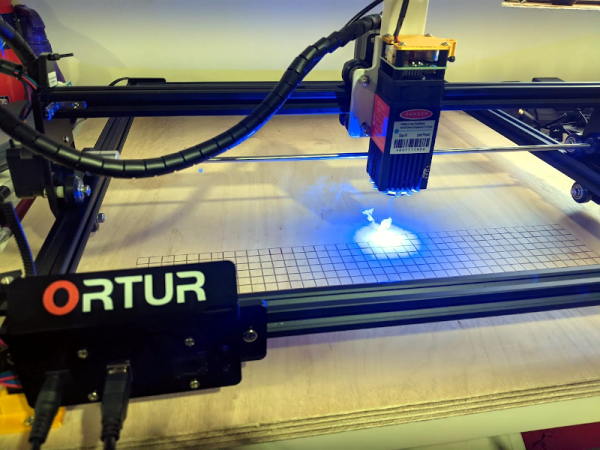

I couldn’t write very much without a computer. Early in my career, I wrote with a typewriter. Unless you are pretty close to perfect — I’m not — it is very frustrating to make edits on typewritten stuff. The equivalent in the real world, for me, has been 3D printers and CNC machines. I can visualize a lot of things that I’m not careful enough to build with normal tools. Despite my 7th-grade shop teacher’s best efforts, everything I did turned out to be a toothpick or a number 7. But I can get my ideas into CAD and from there the machines do the rest. That’s why I was excited to get a laser cutter this past Christmas. You might wonder why I’d need a laser cutter if I have the other tools. Then again, if you read Hackaday, you probably don’t need me to explain why you need a new gadget. I’ve had my eye on a laser for a good long time, but recent developments made it more attractive. I thought I’d share with you some of what I’ve found getting started with the Ortur laser cutter. The cutter is easy to put together and costs somewhere in the $200-$400 range depending on what you get with it. I thought I’d take some time to share what I’ve learned about it.

Why a Laser?

If you haven’t had experience with a laser cutter or engraver before, you might think it is a very specific instrument. Sure, the Ortur is good at engraving some things (but not all things). It can cut some things, too, but not as many things as a big serious laser cutter. However, creative people find lots of ways to use cutting and engraving to produce things you might not expect.