Smart switches are fun, letting you control lights and appliances in your home over the web or even by voice if you’re so inclined. However, they can make day-to-day living more frustrating if they’re not set up properly with regards to your existing light switches. Thankfully, with some simple wiring, it’s possible to make everything play nice.

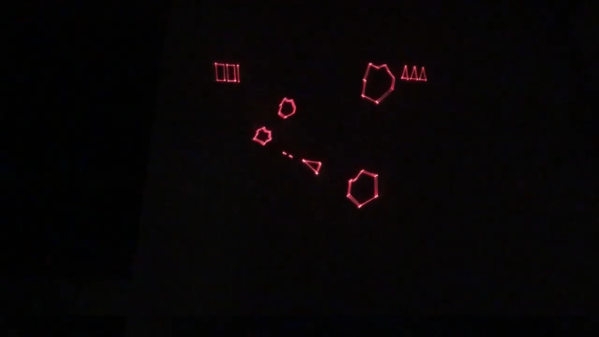

The method is demonstrated here by [MyHomeThings], in which an ESP8266 is used with a relay to create a basic smart switch. However, it’s wired up with a regular light switch in a typical “traveller” multiway switching scheme – just like when you have two traditional light switches controlling the same light at home. To make this work with the ESP8266, though, the microcontroller needs to be able to know the current state of the light. This is done by using a 240V to 3.3V power supply wired up in parallel with the light. When the light is on, the 3.3V supply is on. This supply feeds into a GPIO pin on the ESP8266, letting it know the light’s current state, and allowing it to set its output relay to the correct position as necessary.

This system lets you use smart lighting with traditional switches with less confused flipping, which is a good thing in our book. If you’re using standalone smart bulbs, however, you could consider flashing them with custom firmware to improve functionality. As always, if you’ve got your own neat smart lighting hacks, be sure to let us know!