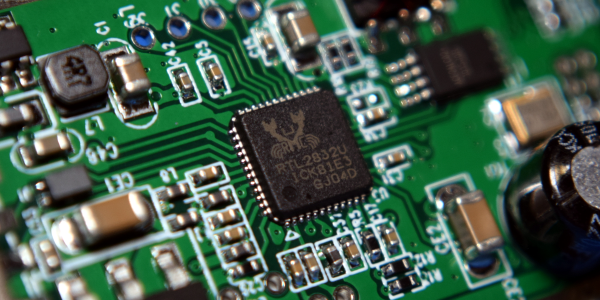

Machinists like to live on the edge, but they always want to know precisely where it is. If you’ve watched any machining videos (*cough*) then you’ve seen heavy use of digital readouts on machines. A “DRO” (as the cool kids call them) is a little computer that knows where the slides are, and thus where your cutter is on the piece. However, there’s a catch. DROs don’t know the absolute position of the spindle, they know the relative position of it. The bottom line is that a DRO is just a fancier version of the graduated scales on the hand wheels. The key difference is that the DRO doesn’t suffer from backlash, because it is measuring the slides directly (via glass scales similar to your digital caliper) rather than inferring position from rotations of the leadscrews. With traditional hand wheels, you have to compensate for backlash every time you change direction, and a DRO saves you from that (among other convenience features).

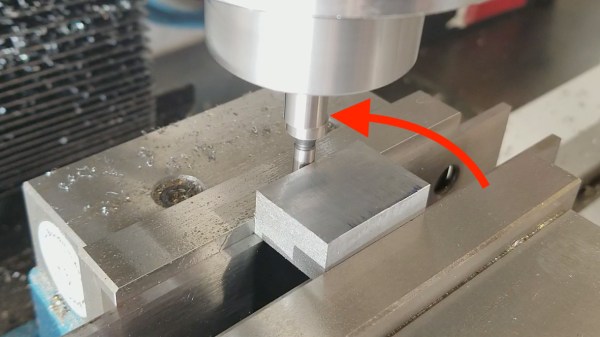

The point is that, whether old school or new, you still only get a relative coordinate system on your part. You need to establish an origin somehow. A useful way to do this is to set an origin at one corner of the part, based on its physical edges. How do you tell the DRO (or hand wheels) where the edges are? Enter the edge finder.