Making one of something is pretty easy, and making ten ain’t too bad. But what if you find yourself trying to make a couple of hundred of something on your home workbench? Suddenly, small timesavers start to pay dividends. For just such a situation, you may find these modular SMD tape feeders remarkably useful.

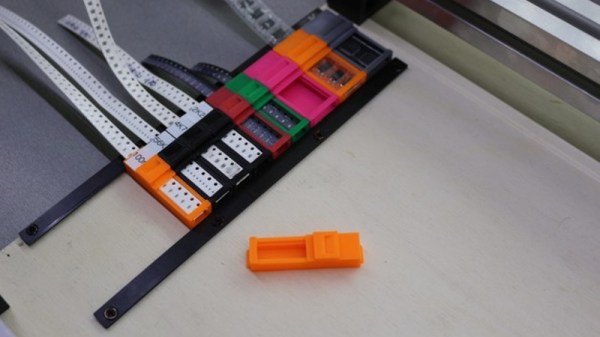

The tape feeders come in a variety of widths, to suit different size tapes. You’ve probably seen if you’ve ever ordered SMD components in quantity from Mouser, Digikey, et al. SMD components typically ship on large tape reels, which are machine fed into automated pick and place machines. However, if you’re doing it yourself in smaller quantities, having these manual tape feeders on your desk can be a huge help. Rather than having scraps of tapes scattered across the working surface, you can instead have them neatly managed at the edge of your bench, providing components as required.

The feeders are modular, so you can stack up as many as you need for a given job. Rails are provided to affix them to the relevant work surface. We’ve seen similar work before – like this 3D-printed bowl feeder for SMD parts.