Hackers love to make music with things that aren’t normally considered musical instruments. We’ve all seen floppy drive orchestras, and the musical abilities of a Tesla coil can be ear-shatteringly impressive. Those are all just for fun, though. It would be nice if there were practical applications for making music from normally non-musical devices.

Thanks to a group of engineers at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, there is now: a magnetic resonance imaging machine that plays soothing music. And we don’t mean music piped into the MRI suite to distract patients from the notoriously noisy exam. The music is actually being played through the gradient coils of the MRI scanner. We covered the inner working of MRI scanners before and discussed why they’re so darn noisy. The noise basically amounts to Lorenz forces mechanically vibrating the gradient coils in the audio frequency range as the machine shapes the powerful magnetic field around the patient’s body. To turn these ear-hammering noises into music, the researchers converted an MP3 of [Yo Yo Ma] playing [Bach]’s “Cello Suite No. 1” into encoding data for the gradient coils. A low-pass filter keeps anything past 4 kHz from getting to the gradient coils, but that works fine for the cello. The video below shows the remarkable fidelity that the coils are capable of reproducing, but the most amazing fact is that the musical modification actually produces diagnostically useful scans.

Our tastes don’t generally run to classical music, but having suffered through more than one head-banging scan, a half-hour of cello music would be a more than welcome change. Here’s hoping the technique gets further refined.

Continue reading “Musical Mod Lets MRI Scanner Soothe The Frazzled Patient”

Are all cheap multimeter leads similarly useless? Not necessarily. [nop head] also purchased the set pictured here. It has no attachments, but was a much better design and had a resistance of only 64 milliohms. Not great, but certainly serviceable and clearly a much better value than the other set.

Are all cheap multimeter leads similarly useless? Not necessarily. [nop head] also purchased the set pictured here. It has no attachments, but was a much better design and had a resistance of only 64 milliohms. Not great, but certainly serviceable and clearly a much better value than the other set.

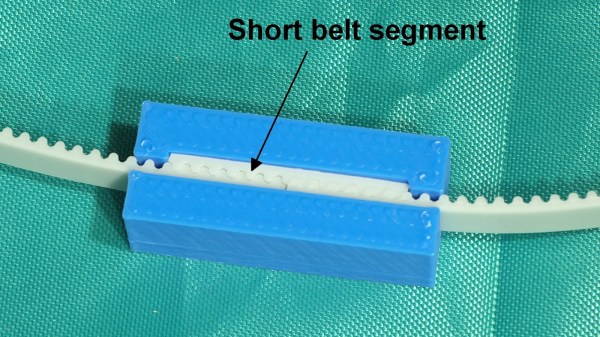

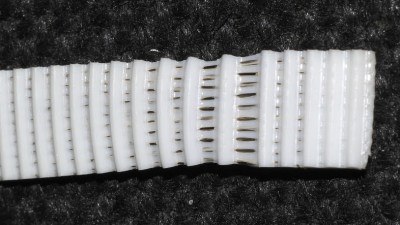

The belts used were common steel-core polyurethane GT2 belts, and the clamp design uses a short segment of the same belt to lock together both ends, as shown above. It’s a simple and effective design, but one that isn’t sustainable in the longer term.

The belts used were common steel-core polyurethane GT2 belts, and the clamp design uses a short segment of the same belt to lock together both ends, as shown above. It’s a simple and effective design, but one that isn’t sustainable in the longer term.