Deep in the heart of your latest project lies a little silicon brain. Much like the brain inside your own bone-plated noggin, your microcontroller needs protection from the outside world from time to time. When it comes to isolating your microcontroller’s sensitive little pins from high voltages, ground loops, or general noise, nothing beats an optocoupler. And while simple on-off control of a device through an optocoupler can be as simple as hooking up an LED, they are not perfect digital devices.

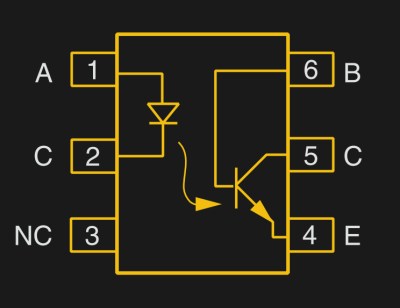

But first a step back. What is an optocoupler anyway? The prototype is an LED and a light-sensitive transistor stuck together in a lightproof case. But there are many choices for the receiver side: photodiodes, BJT phototransistors, MOSFETs, photo-triacs, photo-Darlingtons, and more.

But first a step back. What is an optocoupler anyway? The prototype is an LED and a light-sensitive transistor stuck together in a lightproof case. But there are many choices for the receiver side: photodiodes, BJT phototransistors, MOSFETs, photo-triacs, photo-Darlingtons, and more.

So while implementation details vary, the crux is that your microcontroller turns on an LED, and it’s the light from that LED that activates the other side of the circuit. The only connection between the LED side and the transistor side is non-electrical — light across a small gap — and that provides the rock-solid, one-way isolation.

Continue reading “Optocouplers: Defending Your Microcontroller, MIDI, And A Hot Tip For Speed”

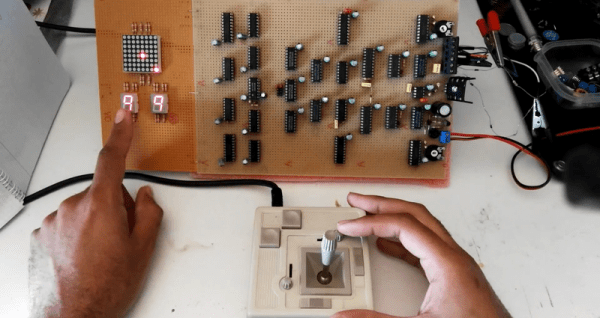

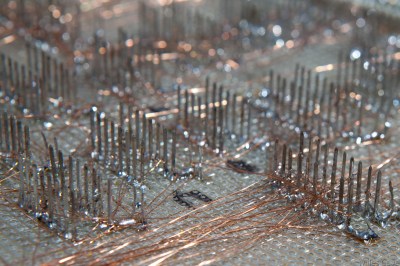

But there’s one more part of this project that amazes us, and that is its construction technique. [OiD] purchased IC sockets with extra long pins and a lot of thin, enamel (insulated) copper wire. A soldering station with a fine tip and high temperature setting allowed him to heat the end of the copper wire to melt its enamel insulation, so it could be soldered to the long pin sockets. Using this method, he assembled the circuit using point-to-point soldering, pretty much like

But there’s one more part of this project that amazes us, and that is its construction technique. [OiD] purchased IC sockets with extra long pins and a lot of thin, enamel (insulated) copper wire. A soldering station with a fine tip and high temperature setting allowed him to heat the end of the copper wire to melt its enamel insulation, so it could be soldered to the long pin sockets. Using this method, he assembled the circuit using point-to-point soldering, pretty much like