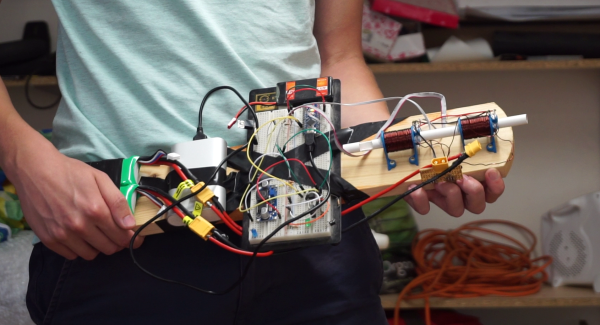

Whenever we see a coil gun project on the Internet, it seems to involve a bank of huge capacitors. [miroslavus] took a different approach with his gun–he wanted his project to be built without those monster caps.

It’s powered by quadcopter LiPo batteries, 2x 1400 MaH drone batteries wired up in series and triggering 21SWG copper coils that [miroslavus] created with the help of a custom 3D-printed winding rig he designed. The rigs have ridges to help you lay the coils down neatly, and they also have mounts for photodiodes, ensuring the gun knows when it’s loaded.

When triggered, the Arduino Nano activates a pair of IRF3205 MOSFETS with logic signals stepped up to 20V, shooting lengths of 7mm or 8mm steel rod. The gun isn’t exactly creating plasma discharges with its launches, but it’s a fascinating project nonetheless.

Check out the disposable camera coil gun project and the coil guns for newbies posts we previously ran.