Badgelife is the celebration of electronic conference badges, a way of life that involves spending far too much time handling the logistics of electronics manufacturing, and an awesome hashtag on Twitter. Badgelife isn’t a new thing; it’s been around for a few years, but every summer we see a massive uptick in the lead up to Def Con.

For the last few years, the designers and engineers deep into Badgelife have had the same conversation dozens of times. One person says, “you know, someone should build a badge that’s a quadcopter.” Another person replies, “Can you imagine how annoying that would be? You’d be putting ten thousand people in a room during the closing ceremonies at DefCon, and a few dozen people would have quadcopters. It would be horrible” Yes, there have been plans to build a quadcopter badge for the last few years, but cooler heads prevailed.

Someone finally did it. The wearable electronic conference badge that’s also a quadcopter is finally here. It’s the work of [b1un7], and it’s going to be exactly as annoying as you would expect.

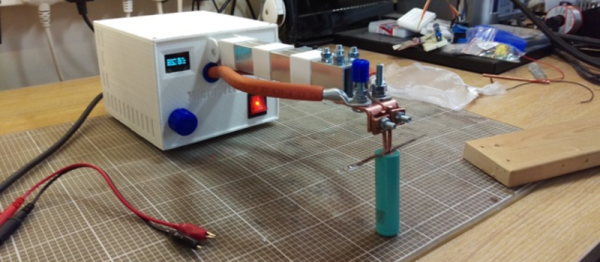

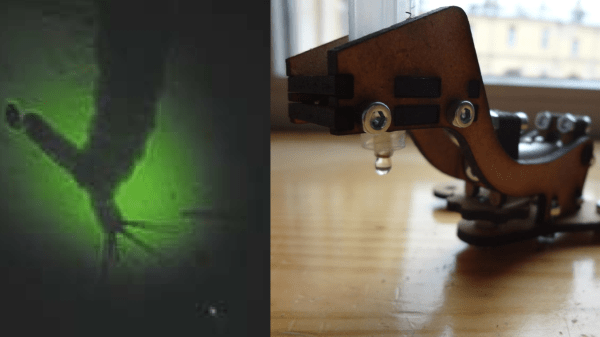

This badge is actually two PCBs, the first being the quadcopter itself, the second being the joystick/controller. The quad is shaped like the familiar jolly roger found in most Whiskey Pirate badges ([b1un7] hangs with that crew), and the controller is a pirate’s treasure map loaded up with joysticks, buttons, and radios. The motors for this quad appear to be brushed, not brushless, and it looks like the arms of the quad have some space for obnoxiously bright LEDs.

This badge is actually two PCBs, the first being the quadcopter itself, the second being the joystick/controller. The quad is shaped like the familiar jolly roger found in most Whiskey Pirate badges ([b1un7] hangs with that crew), and the controller is a pirate’s treasure map loaded up with joysticks, buttons, and radios. The motors for this quad appear to be brushed, not brushless, and it looks like the arms of the quad have some space for obnoxiously bright LEDs.

This is an awesome badge but it’s still [b1un7]’s first attempt at making a badge. Right now, there’s still a bit of work to do — there’s only one week until Defcon — but with any luck [b1un7] will have 25 of these wearable electronic conference badges buzzing around. It’s a terrible idea and we love it.