How any string instrument sounds depends on hundreds of factors; even the tiniest details matter. Seemingly inconsequential things like whether the tree that the wood came from grew on the north slope or south slope of a particular valley make a difference, at least to the trained ear. Add electronics into the mix, as with electric guitars, and that’s a whole other level of choices that directly influence the sound.

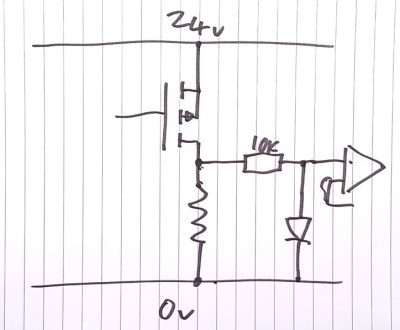

To experiment with that, [Mark Gutierrez] tried rolling some home-brew capacitors for his electric guitar. The cap in question is part of the guitar’s tone circuit, which along with a potentiometer forms a variable low-pass filter. A rich folklore has developed over the years around these circuits and the best way to implement them, and there are any number of commercially available capacitors with the appropriate mojo you can use, for a price.

[Mark]’s take on the tone cap is made with two narrow strips of regular aluminum foil separated by two wider strips of tissue paper, the kind that finds its way into shirt boxes at Christmas. Each of the foil strips gets wrapped around and crimped to a wire lead before the paper is sandwiched between. The whole thing is rolled up into a loose cylinder and soaked in mineral oil, which serves as a dielectric.

To hold the oily jelly roll together, [Mark] tried both and outer skin of heat-shrink tubing with the ends sealed by hot glue, and a 3D printed cylinder. He also experimented with a wax coating to keep the oily bits contained. The video below shows the build process as well as tests of the homebrew cap against a $28 commercial equivalent. There’s a clear difference in tone compared to switching the cap out of the circuit, as well as an audible difference in tone between the two caps. We’ll leave the discussion of which sounds better to those with more qualified ears; fools rush in, after all.

Whatever you think of the sound, it’s pretty cool that you can make working capacitors so easily. Just remember to mark the outer foil lead, lest you spoil everything.

Continue reading “Homebrew Foil And Oil Caps Change Your Guitar’s Tone”