If you wonder how it’s possible to fit a fitness tracker into a ring, well, you’re not alone. [Becky Stern] sent one off to get CT scanned, went at it with a rotary tool, and then she made a video about it with [David Cranor]. (Video embedded below.)

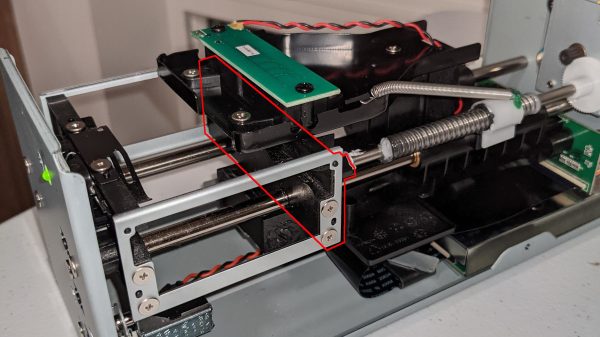

While it’s super cool that you can do a teardown without tearing anything down these days — thanks to the CT scan — most of the analysis is done on a cut-up version of the thing through a normal stereo microscope. Still, the ability to then flip over to a 3D CT scan of the thing is nice.

We absolutely concur with [Becky] and [David] that it’s astounding how much was fit into very little space. Somewhere along the way, [David] muses that the electrical, mechanical, and software design teams must have all worked tightly together on this project to pull it off, and it shows. All along, there’s a nice running dialog on how you know what you’re looking at when tearing at a new device, and it’s nice to look over their shoulders.

Then there’s the bit where [Becky] shows you what a lithium-ion battery pack looks like when you cut it in half. She says it was already mostly discharged, and she didn’t burst into flames. But take it easy out there! (Also, make sure you take your hot xylene out on the patio.)

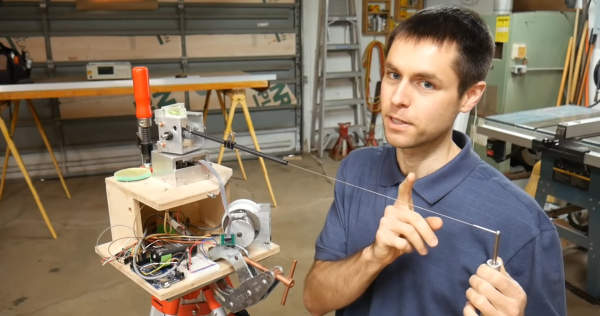

X-ray machines are of course just the coolest thing when doing a teardown. We’ve seen them used from fixing multimeters to simply looking at servo motors.

Continue reading “Becky Stern, David Cranor, And A CT Scanner Vs The Oura Ring”