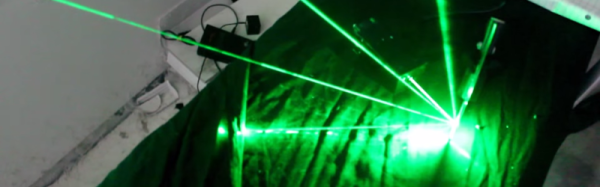

Obviously the wavelength of a laser can’t be measured with a scale as large as that of a carpenter’s tape measure. At least not directly and that’s where a Compact Disc comes in. [Styropyro] uses a CD as a diffraction grating which results in an optical pattern large enough to measure.

A diffraction grating splits a beam of light up into multiple beams whose position is determined by both the wavelength of the light and the properties of the grating. Since we don’t know the properties of the grating (the CD) to start, [Styropyro] uses a green laser as reference. This works for a couple of reasons; the green laser’s properties don’t change with heat and it’s wavelength is already known.

It’s all about the triangles. Well, really it’s all about the math and the math is all about the triangles. For those that don’t rock out on special characters [Styropyro] does a great job of not only explaining what each symbol stands for, but applying it (on camera in video below) to the control experiment. Measure the sides of the triangle, then use simple trigonometry to determine the slit distance of the CD. This was the one missing datum that he turns around and uses to measure and determine his unknown laser wavelength.

Continue reading “Measure Laser Wavelength With A CD And A Tape Measure”

Like most hardware builds for Kerbal Space Program, [lawnmowerlatte] is using a few user-made plugins for

Like most hardware builds for Kerbal Space Program, [lawnmowerlatte] is using a few user-made plugins for  [Gabriel]

[Gabriel]