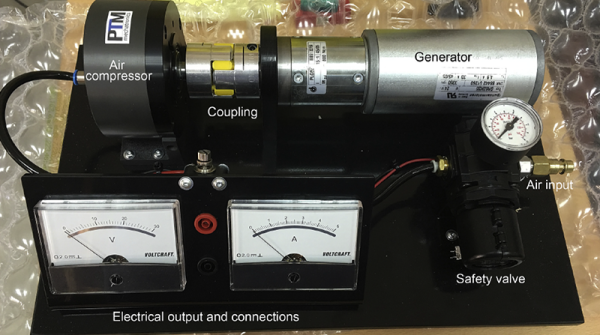

The K40 laser cutter has become ubiquitous in hackerspaces and well-equipped home workshops over the past few years, as a relatively inexpensive introduction to laser cutting and a machine that is readily hackable. Tokyo Hackerspace have one, but sadly their laser tube failed after relatively little use. Replacing a laser tube might be a routine component change for some readers, but it’s still worth looking at in some detail.

Their tube had failed at its output lens cooling cap, a component that is glued onto the end of the tube rather than bonded, and which had snapped off. There had been no mechanical stress upon it, but it was found that the arrangement of their cooling system caused it to drain between uses and thus air bubbles could accumulate. The resulting cooling inefficiency caused enough thermal stress for the bond between the tube and the end piece to fail.

The in-depth analysis of what caused the failure and step-by-step description of the procedure should be of interest to any K40 owner. Little things such as ensuring that the tube is rotated to the right angle for all air bubbles to make their way out of it, or making sure that when the pump is switched off the water isn’t all pulled out of it by gravity seem obvious, but these are traps that will have caught more than one K40 owner.

We’ve covered many K40 stories over the years, but a good place to start for the novice might be this commissioning story, or even this tale of a hackerspace’s modifications to their model.