One easy way to get started on the home automation front is with something that makes a house a home in the first place — lush, green plants. As nice as it is to have them around, it can be difficult to care (or remember to care) for them all the time.

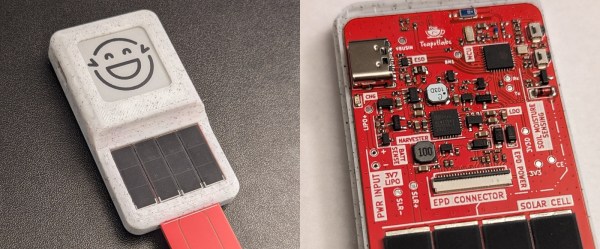

Plantpal makes easy work of that, with an e-paper display that makes it plain as day how your plant is feeling. As you might expect, it features a soil moisture sensor, but what might be unexpected is that it’s capacitive instead of the usual resistive type. This way, no traces are exposed to the elements of plant life. It also has a BME688 sensor to monitor air quality and CO₂, so your plant has the chance to thrive.

Around back you’ll find an ESP32-C6, an AEM10941 for solar energy harvesting, and another set of solar panels. Be sure to check out the project’s GitHub if you want to learn more about this adorable and useful device.