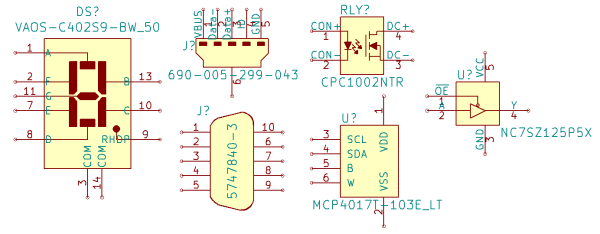

Everyone recognizes Tetris, even when it’s tiny Tetris played sideways on a business card. [Michael Teeuw] designed these PCBs and they sport small OLED screens to display contact info. The Tetris game is actually a hidden easter egg; a long press on one of the buttons starts it up.

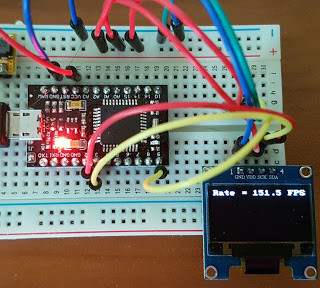

It turns out that getting a playable Tetris onto the ATtiny85 microcontroller was a challenge. Drawing lines and shapes is easy with resources like TinyOLED or Adafruit’s SSD1306 library, but to draw those realtime graphics onto the 128×32 OLED using that method requires a buffer size that wouldn’t fit the ATtiny85’s available RAM.

It turns out that getting a playable Tetris onto the ATtiny85 microcontroller was a challenge. Drawing lines and shapes is easy with resources like TinyOLED or Adafruit’s SSD1306 library, but to draw those realtime graphics onto the 128×32 OLED using that method requires a buffer size that wouldn’t fit the ATtiny85’s available RAM.

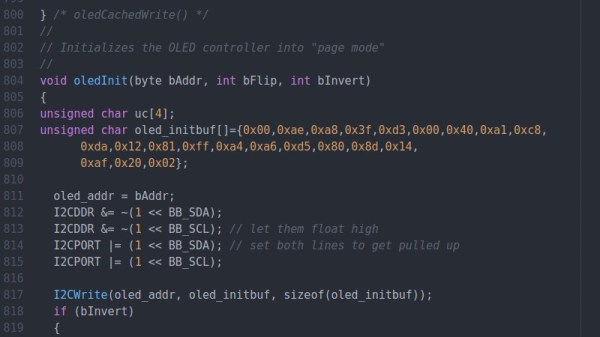

To solve this problem, [Michael] avoids the need for a screen buffer by calculating the data to be written to the OLED on the fly. In addition, the fact that the smallest possible element is a 4×4 pixel square reduces the overall memory needed to track the screen contents. As a result, the usual required chunk of memory to use as a screen buffer is avoided. [Michael] also detailed the PCB design and board assembly phases for those of you interested in the process of putting together the cards using a combination of hot air reflow and hand soldering.

PCB business cards showcase all kinds of cleverness. The Magic 8-Ball Business Card is refreshingly concise, and the project that became the Arduboy had milled cutouts to better fit components, keeping everything super slim.