Today’s hack is an unexpected but appreciated contribution from members of the iFixit crew, published by [Shahram Mokhtari]. This is an ROG Ally Asus-produced handheld gaming console mod that has you upgrade the battery to an aftermarket battery from an Asus laptop to double your battery life (40 Wh to 88 Wh).

There are two main things you need to do: replace the back cover with a 3D printed version that accommodates the new battery, and move the battery wires into the shell of an old connector. No soldering or crimping needed — just take the wires out of the old connector, one by one, and put them into a new connector. Once that is done and you reassemble your handheld, everything just works; the battery is recognized by the OS, can be charged, runs the handheld wonderfully all the same, and the only downside is that your ROG Ally becomes a bit thicker.

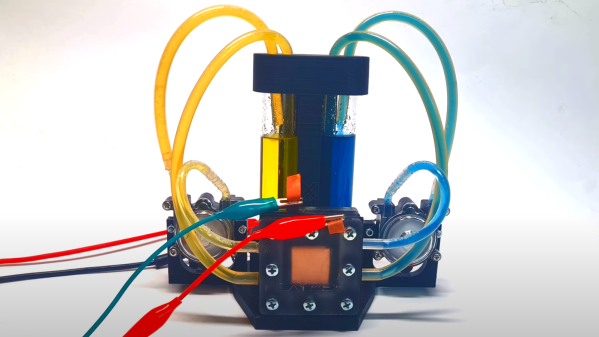

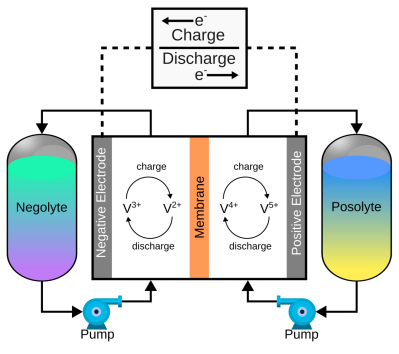

of a pair of electrolytes. These are held externally to the cell and connected with a pair of pumps. The capacity of a flow battery depends not upon the electrodes but instead the volume and concentration of the electrolyte, which means, for stationary installations, to increase storage, you need a bigger pair of tanks. There are even 4 MWh containerised flow batteries installed in various locations where the storage of renewable-derived energy needs a buffer to smooth out the power flow. The neat thing about vanadium flow batteries is centred around the versatility of vanadium itself. It can exist in four stable oxidation states so that a flow battery can utilise it for both sides of the reaction cell.

of a pair of electrolytes. These are held externally to the cell and connected with a pair of pumps. The capacity of a flow battery depends not upon the electrodes but instead the volume and concentration of the electrolyte, which means, for stationary installations, to increase storage, you need a bigger pair of tanks. There are even 4 MWh containerised flow batteries installed in various locations where the storage of renewable-derived energy needs a buffer to smooth out the power flow. The neat thing about vanadium flow batteries is centred around the versatility of vanadium itself. It can exist in four stable oxidation states so that a flow battery can utilise it for both sides of the reaction cell.