Turbine cars never quite came to be, despite many experiments in the 20th century. Despite their high power output for their size, they’re just not well suited to land transport applications; even the M1A1 tank has been much maligned for its turbine power plant. That didn’t stop [Warped Perception] for throwing a jet on the back of a kart though, and it looks like a whole lot of fun. (Video, embedded below.)

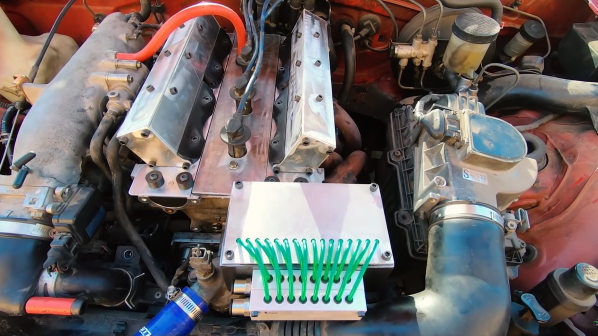

The build starts with a garden variety gokart, with the piston engine and all associated running gear stripped off in haste. The RC-sized turbo jet is then mounted on an elegant aluminium bracket, neatly welded on to the back of the car. It’s hooked up with its electronic controller, with throttle controlled by an RC transmitter. It’s not ideal trying to steer one-handed with another on the stick, but these are the sacrifices made when parts don’t arrive in time.

Early testing revealed issues with air ingestion into the fuel line over bumps, but overall performance was impressive. Future plans involve a top speed run which we can’t wait to see. Of course, if it’s not outrageous enough for your taste, consider [Colin Furze’s] pulsejet build.