Mainstream productivity software from the big companies is usually pretty tight, these days. Large open source projects are also to a similar standard when it comes to look and feel, as well as functionality. It’s when you dive into more niche applications that you start finding ugly, buggy software, and CNC machining can be one of those niches. MillDroid is a CNC software platform designed by someone who had simply had enough, and decided to strike out on their own.

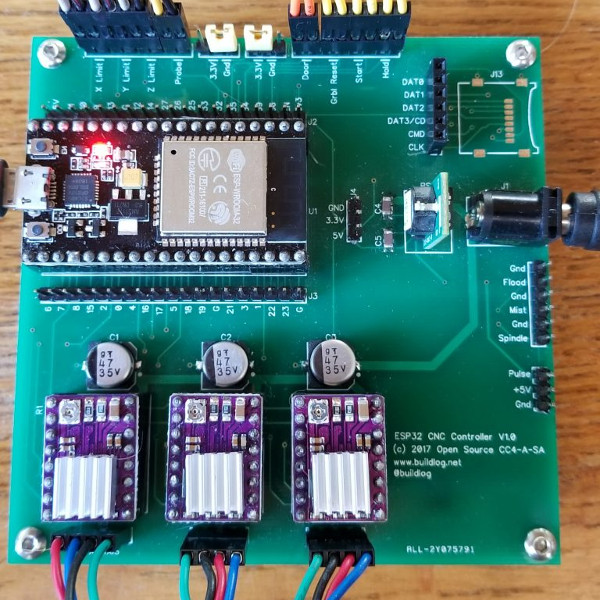

The build began with the developer sourcing some KFLOP motion control boards from Dynomotion. These boards aren’t cheap, but pack 16MB of RAM, a 100-gate FPGA, and a microcontroller with DSP hardware that allows the boards to control a variety of types of motor in real time. These boards have the capability to read GCODE and take the load off of the computer delivering the instructions. With the developer wanting to build something robust that moved beyond the ’90s style of parallel port control, these boards were the key to the whole show, also bringing the benefit of being USB compatible and readily usable with modern programming languages.

To keep things manageable and to speed development, the program was split into modules and coded using the author’s existing “Skeleton Framework” for windowed applications. These modules include a digital readout, a jogging control panel, as well as a tool for editing G-code inside the application.

For the beginner, it’s likely quite dense, and for the professional machinist, industry standard tools may well surpass what’s being done here. But for the home CNC builder who is sick of mucking around with buggy, unmaintained software from here and there, it’s a project that shows it doesn’t have to be that bad. We look forward to seeing what comes next!

Want to see what else is out there? We’ve done a run down of DIY-appropriate CNC software, too.