While there’s still a market for older analog devices such as vinyl records, clocks, and vacuum-tube-powered radio transmitters, a large fraction of these things have become largely digital over the years. There is a certain feel to older devices though which some prefer over their newer, digital counterparts. This is true of the camera world as well, where some still take pictures on film and develop in darkrooms, but if this is too much of a hassle, yet you still appreciate older analog cameras, then this Leica film camera converted to digital might just attract your focus.

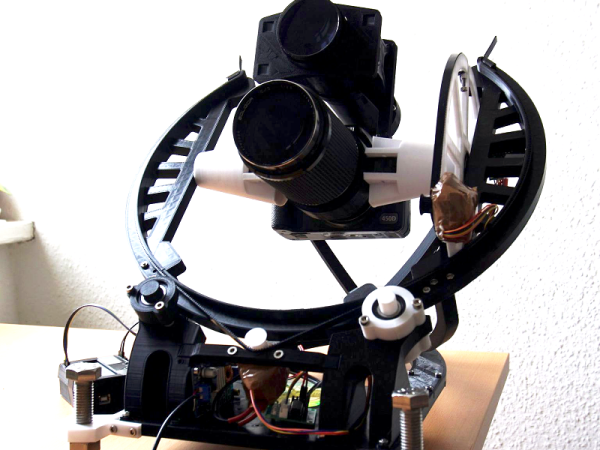

This modification comes in two varieties for users with slightly different preferences. One uses a Sony NEX-5 sensor which clips onto the camera and preserves almost all of the inner workings, and the aesthetic, of the original. This sensor isn’t full-frame though, so if that’s a requirement the second option is one with an A7 sensor which requires extensive camera modification (but still preserves the original rangefinder, an almost $700 part even today). Each one has taken care of all of the new digital workings without a screen, with the original film advance, shutters, and other HIDs of their time modified for the new digital world.

The finish of these cameras is exceptional, with every detail considered. The plans aren’t open source, but we have a hard time taking issue with that for the artistry this particular build. This is a modification done to a lot of cameras, but seldom with so much attention paid to the “feel” of the original camera.

Thanks to [Johannes] for the tip!