Drones that charge right on the power lines they inspect is a promising concept, but comes with plenty of challenges. The Drone Infrastructure Inspection and Interaction (Diii) Group of the University of South Denmark is tackling these challenges head-on.

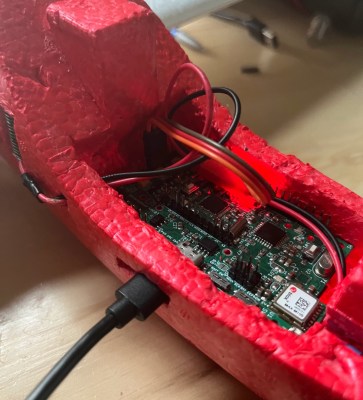

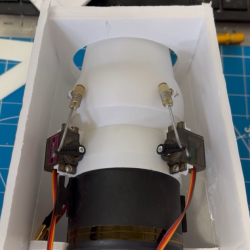

The gripper for these drones may seem fairly straightforward, but it needs to inductively charge, grip, and detach reliably while remaining simple and lightweight. To attach to a power line, the drone pushes against it, triggering a cord to pull the gripper closed. This gripper is held closed electromagnetically using energy harvested from the power line or the drone’s battery if the line is off. Ingeniously, this means that if there’s an electronics failure, the gripper will automatically release, avoiding situations where linemen would need to rescue a stuck drone.Accurately mapping power lines in 3D space for autonomous operation presents another hurdle. The team successfully tested mmWave radar for this purpose, which proves to be a lightweight and cost-efficient alternative to solutions like LiDAR.

We briefly covered this project earlier this year when details were limited. Energy harvesting from power lines isn’t new; we’ve seen similar concepts applied in government-sanctioned spy cameras and border patrol drones. Drones are not only used for inspecting power lines but also for more adventurous tasks like clearing debris off them with fire. Continue reading “The Challenges Of Charging Drones From Power Lines”